CHAPTER I

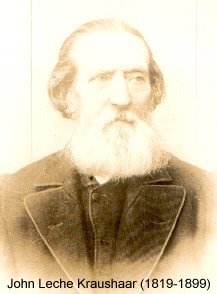

In an old book of Luther's sermons, once in the possession of John Leche Kraushaar, the following entry is recorded:

"John Conrad Kraushaar and Catherina Elizabeth Ninau entered into the state of Holy Matrimony in the year of our Lord 1772, April 29th."

These were the grandparents of John Leche Kraushaar who, being earnest Lutherans, left their home in the Harz Mountains, Hanover, to escape from Roman Catholic persecution, and came to the shores of England, settling finally in London. Their son, John Matthew Kraushaar, obtained employment with the firm of the Barons Oppenheim, merchant furriers in London. The two families had been close friends in the fatherland and John Matthew Kraushaar, being a clever linguist and conversant with five different languages, became confidential clerk, then foreign correspondent and, finally, manager to the firm's business in London. He was a man of strict integrity, severe towards anything that diverged in any way from the code which he considered a consistent rule of uprightness.

The London home at Walker's Terrace (his home after marriage) was one of refinement; the family was expected to appear at late dinner in evening dress, and their leisure time was spent in the cultivation of music in which, like so many Germans, they were all very talented; many of the brothers possessing fine voices and being able to play various instruments. The only daughter, Jane, was her father's favourite and upon her shoulders rested the responsibility of entertaining the guests who came to participate in the evenings devoted to music and literature. Adela Frances Jane Geyden-Roberts (a grandchild, the daughter of the eldest son of the family) recalls in her Memoirs the happy visits she paid to this house. She remembers her grandfather "looking quite oriental" in his smoking cap and dressing gown, smoking his long Meerschaum pipe; her walks in the London parks with "Aunt Jane", who was particular to visit the florist's to obtain her father's favourite moss roses for the table. "Aunt Jane", with her inherent love of beautiful music, would rest in the afternoons with the window opened widely and an Aeolian harp playing sweet chords as the breeze lightly brushed across the strings.

Apparently, with all his admiration for strict adherence to the rules of society, John Matthew Kraushaar made no particular profession of religious observance and it was left to the grandparents, whose faith had been tried in the fires of persecution, to teach and lead his children into the knowledge of God. The grandmother, in Lutheran simplicity, very soon initiated John, the eldest grandchild, into the value of prayer; as early as five years of age, he remembered making his personal needs and desires a matter of prayer (this is told in a charming little book, "The Lost Key", by J.L.K.).

There is not much information about other members of the Kraushaar family who remained behind in Germany. Some members of the family followed a military career. Major-General von Kraushaar and Lieutenant Kraushaar (a nephew of the Major-General) were at the Military College in Erfurt; the Major-General was in command of the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division, 12th Royal Saxon Army Corps. The Brigade consisted of the 1st and 2nd Grenadier Regiments. He was killed in battle before the capture of Sedan, in an attack on the French in the year 1870. Lieutenant Kraushaar was in the Sharpshooters' Regiment. This branch of the family had property in Saxony, and the pre-fix "von", which also appears in books and papers of the Hanoverian branch of the family, is well known as a distinctive title in Germany (of the aristocracy). (F.G.-R.)

No reference has been made to Mrs John Matthew Kraushaar. It is here that the English element is introduced, for Jane Charlotte Prenton, afterwards Mrs J. M. Kraushaar, was a member of a very old English family, having their family seat in Cheshire. The Prentons were united in marriage with the Leches of Carden Hall, Cheshire, about a generation before Jane Charlotte's time, her grandmother being a Miss Leche.

Carden Hall, the beautiful old family mansion standing in acres of park land, with its gates ornamented with the family arms, its lofty ceilings emblazoned with heraldic signs and the walls hung with oil paintings of the ancestors for many generations, was burnt down in about the year 1912, but the old Leche house in Chester can still be seen and is open to the public as a monument of ancient times. Its ownership by the Leche family dates back to about 1550; it was their "town house" before it became fashionable to have one in London, now restored and owned by the City of Chester. The dining hall has been divided in half, so lofty was the ceiling, and the top of the huge mantelpiece can be inspected in the room above. This mantelpiece has the family coat of arms, four crowns, carved upon it and the motto "Alba Corona Fidissimo" (A white crown for the most faithful). The history of this coat of arms and motto is interesting. Sir John Leche, Knight, went to the wars as an equerry to the Black Prince; for his valour and faithfulness in service, the Prince gave him this motto and the four crowns to be emblazoned upon his shield.

John Prenton, father of Mrs J. M. Kraushaar, went as a cadet to India. Later he was given a post at India House but he was wild and profligate; married without consulting his guardians at an early age, and died at 30 years of age, leaving a widow and two little girls.

He having no male issue, the properties passed to another branch of the family but an allowance was made by the guardians to enable Mrs Prenton to maintain and educate her children. John Prenton's father was Attorney of Chester and his house, Stretton Hall, is still standing. Undoubtedly the son inherited his traits of profligacy and extravagance from his father, as the latter was given to gambling, horse racing, etc. He died suddenly while his children were still young, and they were then brought up at Plas Power Castle, Denbighshire, the home of their uncle, Mr Fitz-Hugh, who was appointed their guardian in the father's will.

CHAPTER II

It has been mentioned previously how happy were the family's social gatherings at Walker's Terrace with the pursuit of music as a hobby, and that good literature and poetry also formed a very important part of the leisure moments of the family and their circle of friends. Jane Kraushaar, at this time, introduced into this circle a school friend whose similarity of tastes coincided with those of herself and her brothers. This friend was Frances Jane Thurtell-Murray. Particularly skilful at the piano, she was greatly in demand to play the accompaniments to the songs and instrumental music which they all enjoyed so much. Of a nature in extreme contrast to her friend, perhaps demonstrating the old saying that opposites are attracted to each other, Frances Murray was of a very gentle, retiring disposition, whereas Jane Kraushaar was somewhat spoilt and, being a great favourite with her father and brothers, her character was inclined to be imperious.

The friendship was a lasting one, and continued after Frances left London and went for a time to Yorkshire, letters being exchanged with her friend during the period of her absence. And since, at a later date, the friendship was to become something of a closer nature through the uniting of John with Frances in a very happy and romantic engagement followed by marriage, let us look for a time into the Thurtell-Murray home.

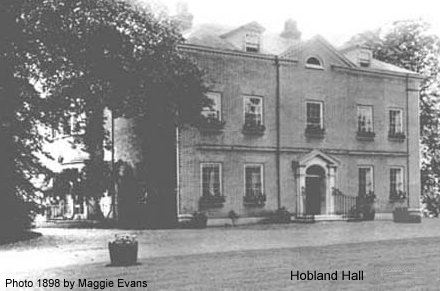

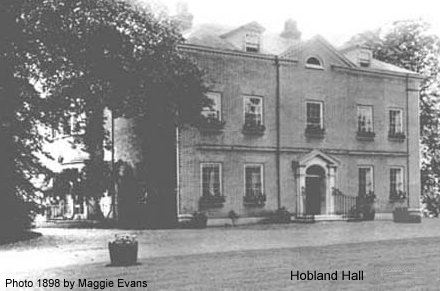

Mr James Thurtell-Murray was the son of a Norfolk squire. There was a large family of twelve brothers and sisters, and the old home was at Hobland Hall, Hopton, Norfolk. James, the father of Frances, was a student, a dreamer, a lover of books and learning. He was a school master, and wrote a book on his own methods of teaching English.

His brother Edward went to sea as a midshipman. His father's advice to him ere sailing was worthy of note. These were his words:- "Do not begin card playing, but provide yourself beforehand with some sensible books which will improve the mind." He took with him Rollins' "Ancient History" and Gibbon's "Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire". Only one of his shipmates possessed a Bible, and Edward borrowed it to turn to some references he came across in reading Rollins. In a wonderful sense, the borrowed Bible proved to be the dynamic which changed his career. His son, in writing a Memoir of his life years afterwards, says: "It is uncertain at what period, and under what circumstances, he first experienced that awakening of the spirit to the importance of a Christian life, and the necessity of a present preparation for a future state or existence, which ultimately absorbed his whole being and exercised such a remarkable influence on the future course of his life. "The wind bloweth where it listeth and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, nor whither it goeth; so is everyone that is born of the Spirit." John, 3:8. For his own part, he always attributed his first serious impression of Divine things to the simple and unassisted perusal of the sacred Scriptures, of which only a single and neglected copy could be found on the vessel.

At thirteen years of age, Edward Thurtell was placed in command, with eight men under him, of a small Dutch vessel which had been captured off the coast of Holland. This was in 1807, but it was not until 1815 that he obtained his commission as a lieutenant, and he soon retired from the Service and was ordained at Norwich Cathedral in 1820. After various curacies, he was appointed to the living at Leck, near Kirby Lonsdale, and was in charge of Religious Instruction at the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowen Bridge at the time that Charlotte Bronte and her sisters were there, so they must have been under his instruction. He remained in this living for twelve years, and was later at Caton, Lancashire, for eleven years. Here he died, and a tablet in the church bears the following inscription:-

"To the memory of Edward Thurtell". Eleven years perpetual curate of this chapelry. He died at Caton Parsonage on the thirteenth February, 1852, in the 58th year of his age. "I have waited for Thy Salvation, O Lord." Gen. 49:18. As a token of affectionate regard this tablet is erected by his parishioners."

Another son of the Thurtells of Hobland Hall was Alexander. Educated at Caius College Cambridge, he gained his mathematical tripos there, thus becoming Senior Wrangler. Two of his daughters, the Miss Thurtells of Hobland Hall, married their cousins, two brothers, both becoming Mrs Everitt. One lived at Cove Hall, Lowestoft, and a third sister was Mrs Browne of Norton Hall, but the branch of the family more closely followed in this account is that of James Thurtell (later known as James Thurtell-Murray, for family reasons), schoolmaster, and the father of Mrs J. L. Kraushaar. His wife, formerly Sarah Holt of Lexton [Lexden], Colchester, was engaged as governess to his cousins. Her grandfather, Rev. John Gordon, Rector of Assington, Suffolk, is recorded in an old gazetteer as having bequeathed £100 to be used in the education of poor children in the parish in which he ministered.

During the time that Sarah Holt was teaching the cousins of James Thurtell-Murray, the parents of her pupils went away for a time leaving her in charge of her pupils and the house and servants. To her surprise and rather to her annoyance, James, then a young man, arrived unexpectedly during one of these days on horseback, and stayed to lunch. After lunch, when Miss Holt was preparing to take the children for a walk, he joined them. She considered that he was over-stepping the bounds of etiquette in doing so uninvited, and showed her resentment by her cool reception of his society. The walk being over and his overtures meeting with absolutely no response, he decided to take his departure but, ere doing so, he hurriedly wrote her a note, opened the schoolroom door and placing it before her without any comment, jumped on his horse and rode away. The note contained a definite offer of marriage which, somewhat to his surprise, was answered favourably a few days later. The culmination of this rather unusual courtship was a very happy marriage, but his wife was afterwards known to tease him about his eccentric proceedings on that fateful day. It was from this home that Frances Thurtell-Murray came as the friend of Jane Kraushaar, and becoming later the wife of the eldest son of the family, John. An old autograph album, still in the possession of one of their descendants, contains little sonnets and hand painted pictures and sketches in ink in which they recorded their promises to each other, and the romantic affection which existed between them.

CHAPTER III

There were several brothers and sisters in the Thurtell-Murray household; of the three girls, Anne, the eldest, was very strong-minded and clever. She had a dominating personality in contrast to the very gentle nature of her sister Frances. The third daughter, Josephine, died at the age of twenty-three. She was of a rather restless disposition, her mind being capable of deep intellectual power leading her to follow an unsettling reasoning pathway in the realm of thought. In her quest for knowledge, her deep reading led her gradually away from the simple faith and acceptance of standards which had been implanted in her by her parents, causing her great unrest and dissatisfaction. When the illness which brought her young life to its termination had laid her aside, she was recalled to her former trust in God through a personal talk with her brother-in-law (J. L. Kraushaar) who, by that time, had given his life entirely to work for God. He, foreseeing that Josephine was not likely to rally from her weak state, pressed upon her very urgently the claims of the Saviour, leaving her with the verse for her meditation: "Whosoever shall call upon the Name of he Lord shall be saved". Upon this verse she rested and, her quest for a solution of her problems having found a satisfactory anchorage, she peacefully and trustfully fell asleep. The words of the text which had brought her peace are inscribed upon her tombstone in Abney Park Cemetery.

Reference has been made to Anne, the practical, strong-minded sister of the family. She married twice, first to Mr Knox-Davis who, very soon after the marriage, died leaving her with one little boy, Elijah. His delicacy from childhood made him, as he grew older, seek health in a warmer climate and so he made his home in Cape Colony, where he practised as a doctor but did not live to middle age, coming to England to die in his mother's home. He left a family of several children.

The second marriage took place some years later, when Anne became the wife of Mr Evans of Brimscombe Court, near Stroud, Gloucestershire. He was a widower and the owner of cloth mills. In the village of Brimscombe, amongst the employees of her husband's mills, Mrs Evans found ample scope for the exercise of her natural gifts, and her influence still remains in that district. She was naturally an organiser, and lasting work of the highest order was carried out for the spiritual welfare and well-being of those with whom she came in contact. She also had a gift for writing, and many booklets were printed and circulated which were the result of her mind and pen. Public speaking was also a strong point with her and though associated with the early Brethren for some years before her marriage with Mr Evans, she exercised this power with complete indifference to their very pronounced views about women speakers.

With all her force of character and determination, she also possessed the very saving quality of a sense of humour, and one of her grandchildren used to describe with great relish how, when caught in any misdemeanour by "Grandma" and expecting a severe lecture, the delight and relief it used to bring when, instead of the stern sense of the enormity of the crime, the humour of the situation would suddenly descend upon her grandmother, who would literally shake with pent-up laughter.

CHAPTER IV

The brothers of the Thurtell-Murray family both went abroad and neither lived to a great age. California was the spot in which they settled. Walter seems to have shared his sister Josephine's restless nature and in his case, too, the necessity of independent thought and reasoning was a strongly marked feature. Dissatisfaction with the constitution and government of England occupied much of his thoughts. At an early age, when a mere boy, he made up his mind to venture abroad and so disciplined himself in order to be able to stand hardship if necessary. His longing for something ephemeral, which he felt had eluded him, as stated in a long poem which he wrote, expressed his desires and hopes and fears. He called it "An Ode to Happiness". Settling in California he took a profound interest in the politics of that country, and became a magistrate. He married a Spanish lady, a Roman Catholic; and their children, Frances, Anita, Mercedes, and Walter are still surviving.

To return to Frances Thurtell-Murray, afterwards Mrs J. L. Kraushaar, it is evident that her parents placed great value upon a good education for their family. The daughters were taught Music by a master who visited the house. Frances was musical, and enjoyed playing the accompaniments to the songs her fiancé and his brothers sang; but found the long sonatas, at which her music master expected her to plod, very wearisome at times; and enjoyed the lighter music in preference to the study of harmony and chords. A French master was obtained to instruct them in that language and, up to the time when well advanced in years, she always kept her mind fresh by reading books in French, conversing when possible in that language; the importance of an early start in French was always claimed by her; and she liked to help her grandchildren with reading and translating from simple books while they were quite small, when they were visiting her. To help Frances and her sister with conversational French, a "mademoiselle" was engaged to teach them waxwork, the fashionable "hand-craft" of their day, and to talk with them in her native tongue. So earnest was her desire to retain her skill in the French language that, after Frances' death, notes made during her reading of idioms, etc., were discovered in her desk by a grand-daughter. Mr Thurtell-Murray made himself responsible for his daughters' education in Arithmetic, and he also kept them interested and well informed on the subject of the political movements of that time. A master visited the house to give the two daughters lessons in dancing and, when well advanced in age, Frances and her husband amused some of their grandchildren by going through the steps and movements of the old minuet which, even after so many years, they had not forgotten.

CHAPTER V

But the happy musical evenings in the Kraushaar home, the dinner parties, the moss roses, the Aeolian harp, are only one side of the picture; John, with his love for music and his natural gift of a good singing voice, decided to have it trained. No doubt this brought him into touch with the theatrical world, the glamour of which, as with any young man in the City, proved a great attraction. His father had rigid rules about the conduct of his house, and he strongly disapproved of any members of the family staying out very late at night. When John began these late hours, trouble soon ensued between him and his father, the father refusing to countenance his son's conduct and, the son neglecting to obey, he was ordered to leave the house.

At this time, he was employed as clerk in a German merchant's office (not the same as his father); he was befriended by his cousins, the Hankeys, who, being desirous of helping him to seek higher things, opened their doors to him. The rift between him and his father, augmented by the sudden collapse of the business house to which he was attached, gave him reason to long for something more satisfying and lasting than he had yet discovered in his quest for pleasure. Through his cousins, he was introduced to a clergyman who interested himself in the spiritual welfare of the young man and, under his influence and through the help rendered by his friend, he came into the great blessing of the realisation of salvation, and the possibility of living a useful life for God.

When the definite step had been taken, the clergyman effected a reconciliation between the father and son and also broached the subject, which seemed to have been laid upon John's heart, of taking a course of study with a view to ordination. Mr Kraushaar gave his consent and study was commenced at the London University. In after years, John always recalled this experience and the knowledge he gained of Greek and Latin as of extreme value in his study of the Bible. It also ever afterward remained with him as a pleasant reminiscence to recollect the students' voices blending in the anthem: "I will arise and go to my Father". He would take up the tune and, in his own rich baritone, would sing it for the pleasure of any friends who happened to be with him.

He took an active interest in the Debating Society at the University, and was elected President. When at last his ordination was approaching, to his father's dismay he had changed his views about becoming a clergyman, and said he felt differently about it. Instead, he decided to apply to the London City Mission for an appointment in one of their districts, and to work among the slums and poor quarters of the great metropolis. He obtained the appointment in one of their districts, St Giles, where he began work. He now felt free to be married, and a busy life of usefulness immediately opened for him. House to house visiting, open air preaching in Cumberland Market, attending death beds (an epidemic of cholera broke out at that time), and wonderful opportunities occurred of pressing home the claims of the Gospel.

At King's Cross, he encountered opposition from atheists and earnest conversations were carried on, a tide of blessing following the faithful witnessing of the Truth. Great movements were afoot in England at that time; and a ready hearing was easily gained by one who knew how to approach; the sincerity of the speaker and the irresistible forces of the message leaving their mark, which proved in after years to be the good seed bearing fruit. Hudson Taylor was at that time preparing himself for the plunge into the vast heathen stronghold of China. The two earnest adventurers met during their student days and Mr Kraushaar could recall an incident when Hudson Taylor, conducting a post-mortem, infected his hand through a small cut with the instrument and was brought to the very gates of death, to be skilfully restored, raised up and enabled to pursue his life objective, the founding of the "China Inland Mission".

CHAPTER VI

At the home in Islington where John L. Kraushaar and his wife lived, educated men, clergy and others used to meet for discussions upon topics pertaining to the spiritual life. The greater majority of the clergy were men who had entered upon their life-work less for a means of livelihood than from a burning zeal and desire to lift the degraded and fallen, to reach the respectable but careless, and to publish the news of salvation. In a large proportion of houses, the Bible was honoured and valued, its guiding principles sought and daily reading was practised. It must have been a few years prior to these informal gatherings of earnest souls, for discussion upon subjects of great moment, that similar gatherings were taking place, also informally, in London, in Ireland and in Plymouth, the motive actuating them being the same as that which promoted Mr Kraushaar and his friends; namely, to seek to put the New Testament principles as practised in the early Apostolic Church into operation.

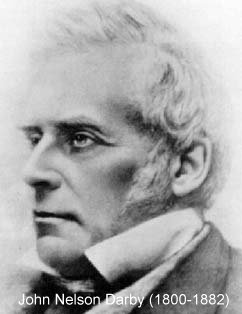

In Dublin, Mr John Nelson Darby, a young man of strong personality, a clergyman in the Church of England, was gathering together eager Christians, many of them clergy, for this purpose and from these movements, which had their beginning in the simplest and most informal way, grew the gatherings which, here and there, up and down the land, met and are meeting still upon the first day of the week, free of any denominational prefix save that given them by others who observed their unobtrusive ways and so called them "the Brethren". The main idea was to gather in the name of the Lord for worship and study of the Scriptures, and to follow as nearly as possible the New Testament principles as set forth in the Epistles and practised in the early Church. Hence no imposing buildings consecrated by Bishop or Prelate were necessary but, as the disciples met in an upper room, so they gathered in private houses, disused halls, in fact anywhere that offered conveniently. Preaching was conducted regularly in their meeting places, as well as in the streets or thoroughfares, in markets, and anywhere that men and women were to be found.

John L. Kraushaar soon came into contact with this movement and, finding that the aims and motives were identically the same as those which he had considered from his perusal of the New Testament, he sought God's guidance in prayer and finally discontinued his association with the Church of England and joined himself with this company. As the result of the informal gatherings spoken of previously, small assemblies were springing up in all parts of the country, meeting regularly for the simple office which became known in New Testament language as "the breaking of bread", following as closely as possible the practices of the early disciples. This took place every week and it became evident that these gatherings needed shepherding and oversight, and also that deeper teaching of Biblical principles was desired and necessary. But a salaried minister was considered contrary to Scriptural teaching, and so it became recognised that, as in the early Apostolic Church, those with the ability to teach were set free for the exercise of this particular gift and were to depend on the resources of God's bounty, their requirements to be made dependent on the voluntary gifts of the circle that was immediately benefiting by the exercise of their ability. George Muller, that grand pioneer of the life of faith and dependence, was beginning his work among the orphans of Bristol and launching further afield in establishing preaching centres in foreign lands. Simultaneously, Mr Anthony Graves, Lord Congleton and others were penetrating into Persia.

All these emerged from small assemblies, whose ideal had been to follow their Lord and the apostolic methods which received their commission from Him.

CHAPTER VII

The London gatherings which had listened to Mr Kraushaar's exposition of the Scriptures now suggested that he should devote himself entirely to ministering, and that some of the scattered assemblies about the country should be placed in his oversight, so that he should develop them and instruct them more fully. After prayer and consideration, he at once resigned his work in the London City Mission to enter upon a different kind of work in the county of Huntingdonshire. His work in the London City Mission had borne the most encouraging fruit, and he had founded a ragged school in a poor quarter of London which he now left established under the supervision of a convert.

It must have been during his life in the Metropolis that he encountered the Bradlaughs, one of whom became a close friend and the other a celebrated politician. In a letter written ten years after his withdrawal into the country, Mr Kraushaar referred to the death of the latter. The circumstances of his death were extremely solemn in view of his professed disbelief. He sank into a coma lasting several days, only to recover consciousness, but without the ability to speak, shortly before his death. His infidel friends used this to support the assertion that Bradlaugh was adhering firmly to his proclaimed unbelief. The other brother clung for comfort to the verses in Job 33, verses 14-24, which he wrote on a card attached to a wreath and sent this to the house where his infidel brother lay dead; his action being a demonstration of his faith that God could answer his prayers for his brother's salvation even during that period of coma when, although outwardly unconscious, the subconscious mind might still be receptive to the voice of God:

"God speaketh once, yea twice, yet man perceiveth it not, in a dream, in a vision of the night; when deep sleep falleth upon men, in slumberings upon the bed. Then He openeth the ears of men, and sealeth their instruction. That He may withdraw man from his purpose, and hide pride from man . . . . That He may be gracious unto Him, and saith: 'Deliver him from going down to the pit. I have found a Ransom.' "

Mr Kraushaar's reference to the above incident is as follows:-

"I have been in correspondence with Bradlaugh and I have sent him a little illustration of Job 33, which you will see in the April number of "Anti-Infidel". Hearing that he had sent that text with a wreath to his dead brother's house, I thought it would comfort him to get evidence, calculated to support his faith; and find from his letter that it had had the desired effect."

CHAPTER VIII

Before leaving the scenes of Mr Kraushaar's labours in the heart of East London, an interesting story is worth recording, in connection with the Ragged School that he developed and finally handed over to the supervision of one who had been brought into a sphere of blessing through his ministry. A costermonger named Bill Newman, who was completely enslaved by drink and longed to be free, confided this desire to Mr Kraushaar, who often had earnest conversations with him during his visits among the courts and poor areas, endeavouring to lift this man from his life of temptation and degradation, to the place of victory over sin. But in spite of his own earnest longing to keep free of his particular weakness, and Mr Kraushaar's repeated efforts to help him, Bill Newman fell again and again. At last Mr Kraushaar resorted to the pledge as a means of help, an expediency he did not frequently employ as he found that, without a real change of heart, it proved a broken reed, the reclaimed drunkard relying upon it solely only to fall again and again. In this case, he explained very simply to Bill Newman that, although powerless of itself to save him from his craving, the pledge would serve as a reminder of his willingness to be free. So determined was the poor man that he solemnly vowed that, if ever he broke the pledge, he would never look Mr Kraushaar in the face again.

Things went well for a time; and then a man, residing in the same court as himself, gave him cause for annoyance. High words soon ended in blows, and a fight was presently in progress. Excitement spread, a crowd formed; Newman won the day; his friends bearing him shoulder high to the nearest public house to "celebrate". Flushed by his success, the hero for the time forgot his promises and pledge, and his fall was complete. True to his word, he kept himself aloof from Mr Kraushaar and, though the latter called repeatedly, he could never catch a glimpse of the costermonger; he was always "out". Neighbours, knowing the circumstances, passed the word from mouth to mouth that "the gentleman was coming" and, long before Mr Kraushaar reached the house, Newman was well away. This happened so repeatedly that there was no doubt as to the reason; and a longing possessed Mr Kraushaar to meet the delinquent face to face and tell him again of the One from whom pardon and peace could be obtained. Timing his next visit at an hour when he knew he would be most likely to find Newman at home, he quickly entered without knocking and was at once face to face with his quarry. Without any preliminaries, he seated himself at the costermonger's side and tenderly talked with him; at first, he was met with the bitter retort "It's no good, sir, you see, it was bred in me. It has grown with me and strengthened with my strength." However, he was persuaded to read the comforting words from Scripture, bringing assurance of peace and pardon for those whose "sorrow worketh repentance", and Mr Kraushaar did not leave him until he was satisfied that Bill Newman was a "new man" in Christ.

This was the testimony years later of a neighbour who, chancing to meet Mr Kraushaar, was asked by him: "Do you remember Bill Newman?" "Yes, sir," was the prompt reply and, in the quick humour natural to the Cockney, he added: "He is in truth a new man". After the change had taken place in Newman's life, he found it quite impossible to carry on his business in the characteristic way of men of his type, plying his wits in competition with others of his trade without regard for straight-forwardness of dealing. Now, he found this kind of thing did not fit with his new life, and to still trade with the determination to keep business within the bounds of honesty seemed impossible; and so very soon he found himself without work.

Mr Kraushaar began to give him lessons, partly to fill up his enforced leisure time, lest in idleness the tempter might again assault him in his weak point; and he proved himself such an apt pupil, so quickly assimilating the studies set before him that, when the time came for Mr Kraushaar to leave London, Newman was well qualified to undertake the position of Headmaster of the ragged school.

CHAPTER IX

Life in the free open country was such a complete change to Mr Kraushaar's family of young children after the rush and turmoil of city life. His eldest daughter, Mrs Geyden-Roberts, describes her first impressions very vividly in her Memoir. She recalls opening very cautiously a dark doorway, and she and her little brother peering with half fearful eyes through the chink, expecting to see a dark passage or a gloomy cavern. Thrilled with joyous amazement, they found that it opened on to a glorious green meadow, with flecks of white, which these poor little town-bred children thought were crumbs thrown out to the birds by some kind people but which were really only daisies! She also remembers vividly her first glimpse of a country boy in a cotton smock, sitting in a cottage chimney corner eating porridge from a basin, and too shy to look up at the two pairs of inquisitive children's eyes gazing at him in profound interest.

Mr Kraushaar had always possessed a great love for animals and had been accustomed to horses from the days when he was a young man in his father's house at Walker's Terrace. His wife declared that the first remembrance she had of him was of his arrival at the front door during one of her early visits to her friend, Jane, his sister, in a smartly turned-out trap drawn by a spirited horse. No marvel then that, when residing in the country with long distances to cover in order to reach the villages and hamlets where he was to preach, he decided that the best mode of getting to his destination was on horseback. On one occasion, after some years had passed since his removal from London, he was asked to visit a hospital, and lying there was a man who was not long for this world. Pausing to speak a kindly word, to his surprise he was accosted by name. "Don't you know me, sir?" Mr Kraushaar could not recall having seen him before, so he went on to explain: "I used to see you at --------, and you used to speak to me about my need of salvation. I got to hate you for what I thought was unnecessary persistence on your part. Religion would mean an alteration in my life, and I had no intention of making a change. At last, my hatred was so intense that I decided I would lie in wait at a certain cross-road past which you would ride on a Sunday night to your preaching appointment. I waited till I heard your horse's hoofs. Just as I was preparing to emerge from my hiding place, I saw you, but you were not alone. There were two riders instead of one; and I had to abandon my intention. I wished to confess this intended crime, but did not know where to find you as, since that evening, I have repented of my wicked designs and would like to tell you so."

Mr Kraushaar felt assured in his heart that the incident was a fulfilment of the promise: "The Angel of the Lord encampeth round about them that fear Him and delivereth them", as he never remembered having ridden that way in company with anyone; he believed that the eyes of his would-be murderer were opened miraculously and, in this way, his life was preserved.

After some years in the Eastern counties of England, the Kraushaars removed to the Midlands and, for a time, resided at Stratford-on-Avon; finally settling in Somersetshire. By this time, the eventide of life was drawing near, and the remoteness of the country seemed ever more enticing. A little hamlet near Wellington was the spot chosen to settle in; and a suitable small house with an orchard and nice kitchen garden with high stone walls, with fig trees spreading upon them, fuchsia shrubs, rosemary bushes and the aromatic fennel bed, are all associated with this spot. A small room was set apart as a study, and there Mr Kraushaar spent many hours of the day. The outlook was the higher part of the kitchen garden where were many fruit trees, apples, plums, etc. In the fork of these trees he fixed boards to serve as bird-tables, and each day bread was placed upon them to entice the birds which came in countless numbers and varieties, to be enjoyed and observed by the occupant of "the den", as the study was whimsically called. Often Mr Kraushaar would go out during feeding time, and the birds got accustomed to his tall, upright figure and, learning that he was a friend, would often come to rest on his shoulders and hands.

It must not be imagined that these declining years were idle ones. The old horse, "Jack", carried his master over many of those remote roads and lanes, he visiting the elderly and sick. This hamlet was unequipped with any place of worship, and the scattered residents in the farms and cottages had become so isolated that there was plenty of scope for work of a spiritual nature amongst them. Mr Kraushaar had made a study of botany and also, jointly with this, of the value and healing to be obtained from many of the herbs and plants. He regularly used this form of medicine himself, and also distributed it among the country people for the cure of various ailments. Every Sunday, the house was open for meetings, and the rooms used to be full of people who came to listen to the unfolding of the Gospel narrative and teaching pertaining to everlasting life.

Another form of activity was the employment of another of his natural gifts, the use of his pen. Some years previously, he decided to help a small printer and publisher, a Christian man who found if difficult to maintain a living, having a collection of articles which he had written for a magazine published at his own expense in book form, refusing to accept any of the proceeds for himself but all to be placed at the disposal of the publisher. The book was called "The Voice of Flowers", and was an examination of the botanical characteristics of many English wild flowers, a lesson of a spiritual nature being drawn from each one. This book in its original form is now out of print; but a greatly abridged and altered edition has been "simplified" for children, and published in Australia, which is a mere travesty of the parent volume, a few copies of which remain still in the possession of relatives.

Several other books emerged from Mr Kraushaar's pen at that time, as well as regular contributions to periodicals. The expense accruing from all this must have been considerable; and his writings being still in demand, a friend gave him a small printing press, which he used to the end of his life, setting his own type and printing a great deal. He printed "The Occasional Magazine " and circulated it, not only in this country but in other lands amongst English-speaking people.

CHAPTER X

Little reference has been made as yet to Mr Kraushaar's family. Two or three children died in infancy but three sons and two daughters grew up, and all except one of the family left the shores of England; both the daughters found their final resting place in other lands, one in Africa and the other in Australia. The son who never left the land of his birth had desired to become a missionary in South America but never had fulfilment, as he was not more than 21 when he died of typhoid fever. He was a very earnest, thoughtful young man, and his absorbing aim to enter upon a life of usefulness as a missionary began and ended in village work amongst lads of the working class. If the thought ever occurred to him that this was trivial compared to his main objective, its wide nature was demonstrated in a way which perhaps would have surprised him. A village boy, over whom he particularly toiled and prayed, who was also his namesake "John", responded in a wonderful way to his earnest, persuasive conversation, and John Kraushaar Junior undertook the self-imposed task of teaching him to read and write, in order that he might be able to study the Bible. Many years later, John Ewen, after his friend's departure with Christ, himself set out on the journey to South America where he worked as a most successful missionary to the end of his life. Those who met up with him on his visits to England for furlough will always remember his tall, slender figure (over six feet), his strikingly cheerful disposition and sunny smile. A little girl of eight years, on one of those occasions, has now, after many years have passed by, a vivid recollection of a missionary meeting at West Buckland, near Wellington; the huge map of South America behind the tall figure of the missionary, his bright face and cheery manner and, above all, his hearty singing voice as he led the company in singing:

"Jesus sought me when a stranger

Wandering from the fold of God

He to rescue me from danger

Interposed his precious blood.

Oh, to grace how great a debtor

Daily I'm constrained to be

Let thy grace, Lord, like a fetter

Bind my wand'ring heart to Thee!"

John Kraushaar, Junior, died breathing a prayer for his youngest sister, then a little girl. He prayed that she might grow up to yield her life to God for service. The abundant answer to this prayer was amply demonstrated. This youngest member of the family had been received with such joy by her parents that her father gave her the name "Grace Beatrice", saying that she was "a blessing given in grace". When all the other members of their family had left home, some having sailed to Australia and established homes of their own, this daughter was left to them and cheered their declining years with the comfort of her presence. Mr Kraushaar used laughingly to call her his "curate", and she took an active part in visiting the cottages and farms, opened a Sunday School for the children of the village and was always associated with everything for the well-being of the poorer members of the place. She was small in build but very active, quick in all her movements, swift to think and to act.

Her father entertained the highest opinion of her ability, and in his letters he used to speak with pride and affection of the esteem with which she was held by the villagers. Always alive to the humorous side to everything, he relates in a letter to his son-in-law Mr J. Geyden-Roberts how, on one occasion, a spring of clear water from the hills, which usually gushed plentifully from a spout on the roadside opposite the house, became impeded in its flow by deposits of sand and dead leaves and a workman from the village voluntarily commenced clearing the debris in order to free the stream once more. An acquaintance passing at the time was overheard to enquire what he was doing. "Well," said the first man, "Mr Kraushaar is a very good man, and his daughter is a better, and they do a lot for us folks here; so I'm doing something for they." To this, Mr Kraushaar adds: "The better has become even "betterer", I fancy, in the estimation of these poor souls."

He relates affectionately how, when returning from one of his hermit's walks, as he termed his daily constitutional, he saw dear "Tricie" wheeling a little deformed child in her chair, the maid who usually attended the child having gone to her dinner, and his daughter undertaking the task of keeping the little invalid happy until her nurse returned. He adds with pride: "Now, you know, nobody else would have taken that trouble."

But his daughter achieved bigger things than these in that quiet district. A labouring man lost his wife and was left with a family of young children. They were very poor, and the father was an uneducated, simple countryman. Their home was very wretched and, in these days of greatly improved conditions, it would have long been "condemned", as the cottage was quite a tumble-down ruin. The poor man, at his wits' end how to manage his family, boarded the girl out with a dreadful old woman who was held in awe by the superstitious country people, whom she managed to persuade that she possessed the power of witchcraft. The poor child became a kind of drudge to this old woman, who treated her cruelly and managed to thoroughly terrorise her. Stories of her treatment began to circulate, and reached the ears of Miss Kraushaar, who quite calmly went on a tour of investigation. As she approached the cottage, sounds of crying confirmed the stories she had heard, and she fearlessly knocked at the door. It was opened by the would-be "witch". "Where is Annie?" demanded Miss Kraushaar. The old woman sought to prevaricate. "Bring her down at once, or I will inform the authorities." This threat had the desired effect, as the mystical reference to "authorities" almost always did: visions of police, magistrates and other officials of a powerful and terrific order were all embodied in the stupendous category of "the authorities". The unhappy child was duly presented in a state of neglect and abject misery. "Now, Annie," said Miss Kraushaar, firmly but quietly, "fetch your things because you are coming away with me." "I'll witch 'ee!" shrilly screeched the old woman, as visions of the loss of the small sum for Annie's "keep", which her poor father managed to eke out of his earnings as compensation to the witch for her trouble, momentarily occurred to her mind. "Rubbish!" said the imperturbable rescuer, and then added "your power of 'Witching', as you call it, is the power of Satan, who delights to harm people, but God is stronger than Satan."

What followed then can best be imagined, but finally Miss Kraushaar triumphantly bore the terrified child away, soothing her with assurances that the witch's threat could never harm her again. It was many months before Annie recovered from the experience of living with the witch. Whether it was the result of the neglect and ill-treatment, or whether it actually was due to a more sinister influence, cannot be definitely stated but the child was for a time subject to a sort of fit, which called for immediate attention as the clenched teeth were in danger of causing serious trouble if the tongue got between and so, at the first intimation that one was coming, a toothbrush had to be inserted to prevent the teeth coming together. The preliminary state before the actual fit was a great excitement, often accompanied by loud singing, burning cheeks, shining eyes; then the fit, and afterwards a death-like stupor lasting for some time. Miss Kraushaar felt that the symptoms were so similar to demon-possession encountered by missionaries in heathen lands where evil influences hold sway; and she was persuaded that the wicked old woman had actual dealings with the Evil One and that, in some way, her influence had left its indelible tracings upon the unfortunate child who had been placed in her care.

During the enforced period of rest and recuperation, Miss Kraushaar trained and equipped Annie for service, helping and teaching her to make the necessary print dresses, aprons, etc., and finally a good situation was found for her which she retained for a number of years, growing into a beautiful woman as to outward appearance, with blue-black wavy hair, dark eyes and features which could compare with any Spanish beauty. Her character [after conversion, which took place at a Gospel meeting held by one of Spurgeon's Evangelists, and after which she never had another fit. F.G.R.] was gentle and kind; and it was no surprise to those who knew her when she became engaged to a tradesman, who emigrated to Canada and, after establishing a business, sent for Annie who is now his valued wife and the mother of two or three children. The family returned to England to visit Annie's old father, with whom she had maintained a one-sided correspondence, several years afterwards. During the years that his daughter had been away, old Matthew had taken her letters to Miss Kraushaar, and used to listen to the reading of them with tears running down his cheeks. He was very fond of his children, and felt his lack of education to be a barrier to remaining in touch with them.

CHAPTER XI

A glimpse of Mr Kraushaar during the later years of his life affords an interesting sidelight; we can best get it through his grandchildren, with whom his memory is still alive. While the elder members of their family were still children, they used to have an occasional visit from their grandfather, and these times were greatly looked forward to as being events of outstanding pleasure, and his tricks and jokes, many of them of a practical nature, created a great diversion in the lives of this family of girls. It was one of his games to compose rhymes about the characteristics and habits of his children, and pretend he had "picked them up in his study". His youngest daughter at that time was almost the same age as her nieces and so came in for her share, too, of the practical joking. A story book about the Siege of Strasbourg contained the following inscription on the flyleaf in pencil in her father's handwriting, and is a sample of the way he employed of amusing these children:

Tricie Kraushaar, her book,

Which to Weymouth she took

And read on the floor like a Turk

The long words she skipped

And the short words she slipped

And so she got right through the work.

But the meaning was hazy

And Tricie was crazy

To learn what each chapter would tell;

So she took it to bed, put it under her head

And dreamt that she saw it right well.

A tribute from one grand-daughter who spent much of her time in her grandparents' home might be quoted. She says: "I think of my grandparents as godly, clever, and loving, cultured and accomplished; of Grandma as exceptionally unselfish, patient and forgiving; of Grandpa as deeply loving, and deeply beloved - growing broader in his love every day, embracing all who love the Lord Jesus and excluding none."

A younger member of the same family of grandchildren remembers first seeing her grandfather when she was six years old. Life in London and in Worcestershire made the visits, especially for the little ones of the group of grandchildren, less frequent on account of distance. As the pony trap neared the house, a tall figure appeared in the doorway, advancing to the garden gate. Mr Kraushaar's hair never went white but was iron grey, and he wore it rather long and brushed straight back from his forehead, while at the sides it curled slightly over his ears. His eyes were very blue, and his figure was tall and erect and slender. He walked with his head thrown slightly back. As the children climbed out of the trap and approached the gate, they were received very affectionately by the tall stranger of whom they had heard their elder sisters talk so much as "Grandpa". His greeting was always in German fashion, as he took their faces between his hands and kissed them first on one cheek and then on the other.

Of the little grandmother, memories are not quite so lucid, possibly on account of her retiring disposition. She was increasingly dreamy and absent-minded as age advanced, a feature which was playfully employed as a means of teasing by her husband. He would quietly remove the contents of her plate at tea-time, while her thoughts were occupied with other things; and when she remarked with surprise at finding that she had finished, thinking there was another piece left, he would smile mischievously as he replaced it from beneath the table-cloth. Sometimes, after the meal had commenced, she would ask: "Have we given thanks?" and he would tersely reply: "We (with emphasis) have." Books never failed to be a source of happy occupation to her; and some of her letters, written in the fine perfect handwriting of her day, with their meticulously perfect English, are still preserved. She outlived her husband by about three years.

Both reached the age of 80; and to both, death came without any premonition or long illness. Just the usual pursuit of a quiet day with its recurring duties, each fulfilled and then laid aside, as if for a night's rest, never to be resumed. Mr Kraushaar left his study, as was his custom, after setting the type in his printing press which he expected to finish the next day, his letters stamped and ready for the post in a pile on the desk. Reaching his room, he collapsed with sudden heart failure. On the previous Sunday, he had spoken with great earnestness from the 12th chapter of Romans: "I beseech you therefore by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, wholly acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service."

Three years later, his wife was laid to rest beside him in the quiet spot at Chelmsyne. In her case, a sudden illness seized her in the night and, ere morning dawned, she had gone. It was as they would both have wished; for they lived so near to God in their earthly life that the change was, as someone has put it, "merely going into another room". "For we know in part, but then we shall know even as we are known."

CONCLUSION

Yesterday, as the writer of this brief Memoir stood in the little graveyard at Chelmsyne, near Wellington, Somerset, some thoughts surrounded her with regard to this life, which she has recorded for the many great-grandchildren of John Leche Kraushaar, which seem to belong partially to these records and so, for this reason, they are being added to them.

There, far away from the bustle of town, the rush of traffic and the tramping of passers-by, is this remote spot. In the background lie the Blackdown Hills, which Mr Kraushaar knew well as his old horse, Jack, carried him to the isolated farms and cottages nestling among them. Leigh Woods are not far off, steeped at this time of year in a haze of bluebells and delicate green beech leaves.

There, far away from the bustle of town, the rush of traffic and the tramping of passers-by, is this remote spot. In the background lie the Blackdown Hills, which Mr Kraushaar knew well as his old horse, Jack, carried him to the isolated farms and cottages nestling among them. Leigh Woods are not far off, steeped at this time of year in a haze of bluebells and delicate green beech leaves.

Few know of this peaceful plot, where rest many pilgrims who once trod life's pathway and, looking on these grassy mounds and simple grey headstones, one felt a momentary pang, a sense of failure. Was this all? To lie forgotten, far from the reach even of those who revere his memory, his grave to be visited and thought of just occasionally, once in many years, with long lapses between. What was the good of it all? The choice of a life of hardship, toil and loneliness, perhaps of misunderstanding; the separation from kinship, brothers, father, mother, sister - was it worthwhile? It might have been so different had he chosen the path of self-advancement, or thought of remunerative values, of the inheritance he might legally have claimed, or even sought to do what was apparently the natural thing following his father's wishes, which would have meant a widely different sphere of work of an undoubtedly useful kind. Ordination in the Church of England, association with people who would have appreciated his talents, the blandishments of society which would have afforded him a welcome position in recognition of his university education, and charm of refinement. Rosier prospects unquestionably, and possibly an inheritance which would have materially benefited those who followed him.

Was he justified in forsaking all these things? All these questions passed in review before the writer's mind as she stood in that quiet spot at Chelmsyne; the answer came almost simultaneously - "It is enough for the disciple that he be as his Master and the servant as his Lord." Our Lord Jesus Christ laid aside everything that He might redeem fallen man; and it is only when we assess values in the light of Calvary that we reach the true viewpoint and realise the immensity of the sacrifice there, and the littleness of earthly things. The blessing promised as the result of obedience was to extend to "thousands of them that love Me", to the third and fourth generation; and if we think, I believe we can see this literally fulfilled in our midst today. John L. Kraushaar's children all grew up fearing God and longing to serve Him to the utmost of their power. Many of his children's children have surrendered their hearts and lives in the same way for service, and so the ever-widening circle goes on like the ripples on a still pond caused by the casting of a pebble. Who can measure the extent to which one life, surrendered in faith and obedience to God, will affect the generations to come? Undreamed of at the time, a small action, made in self-surrender for the sake of the One who gave Himself for us, can be used of God to bring about mighty results.

"Little is much when God is in it

Man's busiest day's not worth God's minute

Much is little everywhere

If God the labour doth not share.

To work with God, nothing is lost;

Who works with Him does best and most."

There, far away from the bustle of town, the rush of traffic and the tramping of passers-by, is this remote spot. In the background lie the Blackdown Hills, which Mr Kraushaar knew well as his old horse, Jack, carried him to the isolated farms and cottages nestling among them. Leigh Woods are not far off, steeped at this time of year in a haze of bluebells and delicate green beech leaves.

There, far away from the bustle of town, the rush of traffic and the tramping of passers-by, is this remote spot. In the background lie the Blackdown Hills, which Mr Kraushaar knew well as his old horse, Jack, carried him to the isolated farms and cottages nestling among them. Leigh Woods are not far off, steeped at this time of year in a haze of bluebells and delicate green beech leaves.