THE CORNISH SETTLEMENT

Text by John Rule

Drawings by Liina Truu

Contents

Byng - The Village That Never Was!

Before The Pioneers

Byng Wesleyan Chapel

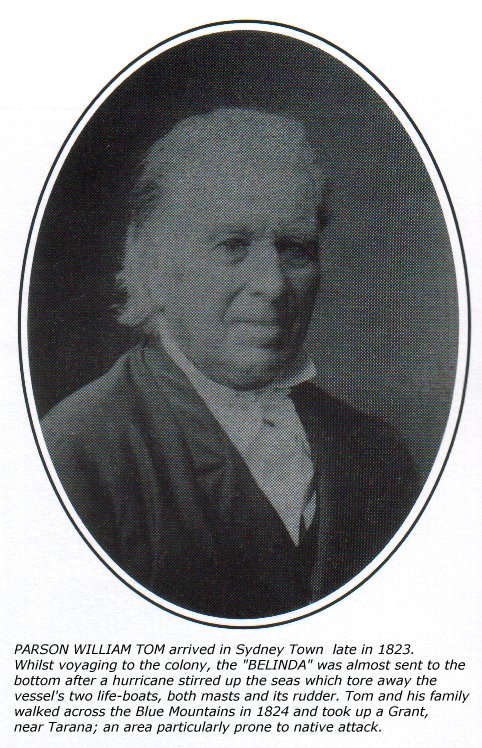

Parson William Tom 1791 - 1883

Springfield

George Hawke 1802 - 1882

Pendarves

John Glasson 1803 - 1890

Bookanan

The Cornish "Cousin Jack" Miners

Byng's Early Copper Mining Era

Discovery Of Australia's First Payable Goldfield

Byng's Era of Company Mining

Cornish Settlement Site Map

BYNG -

The Village That Never Was!Some 240 kilometres west of Sydney, midway between the rural cities of Orange and Bathurst, lie the remains of what was to have been "the village of Byng". From the rolling pasturelands of the Mitchell Highway, the terrain towards Byng quickly changes. Along the way, surrounding hills become dotted with crusty, grey-green basaltic outcrops; indicating a volcanic heritage. There are still a few decaying ruins; now only skeleton-like frames with scattered roofs lying nearby. One or two hay-filled sheds remain, standing at precarious angles, under constant threat of toppling to a similar fate without the slightest provocation. Relics of early farm machinery can also be seen where they were left to rust or rot after outliving their usefulness.

Occasionally, a lost tourist strays down the twisting hawthorn-lined laneway, puzzled by Byng's mystical English-style charm and origin. There is now a certain tranquillity, disturbed only when the wind howls throughout the valley, lending an eerie effect to the otherwise sleepy hollow. Although present-day civilisation seems to have deliberately avoided Byng, one can sense that it has not always been that way.

Byng, or the Cornish Settlement, has been a constant provider for all who have believed in her for the past 150 years. She has seen fortunes won and lost with copper mining and hosted the TRUE discoverers of Australia's first PAYABLE goldfield. Convicts, bushrangers and marauding aborigines are all part of her history. Cattle over-landing, agriculture and religion have also played their part in her earlier and more important days. Byng now remains as a silent witness to history in its making, projecting an image of total despondency.

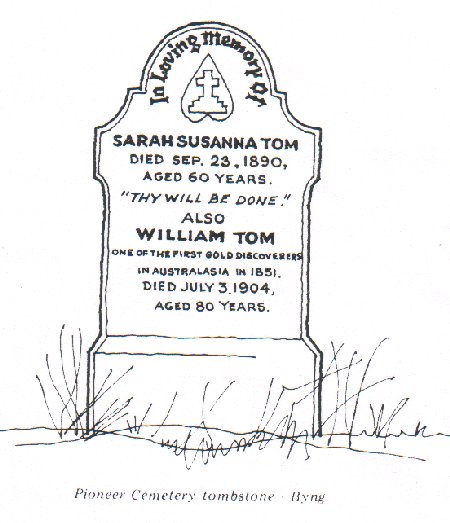

Byng's most prominent feature is an historical church and cemetery where her pioneer identities now lie resting. They are the silent guardians of an eventful, but long-forgotten past; holding the key to many interesting tales of bygone years. Twisting vines and creepers have overtaken many of the ancient tombstones, as if to hide some secret from an outside world that Byng seems anxious to avoid.

High hawthorn hedges still act as inpenetrable barriers, concealing the Cornish Settlement's few remaining homesteads from prying eyes. The original track from Bathurst, that once passed through Byng, has been closed to the public. Government approval has been given for the closure. All roads now surround Byng, but none pass directly through her yester-year precincts.

These pioneer thoroughfares have been reclaimed by land-holders who cherish their heritage, rather than the curiosity of an outside world that has more than once disappointed Byng. Pioneers, convicts, goldseekers, copper miners and disappointments. They are all part of the passing pageant witnessed by Byng, which now remains to ponder what the next century and a quarter will bring.

During 1852, Governor FitzRoy approved of a special area being set aside for the building of a Wesleyan Chapel, school and cemetery at the Cornish Settlement. The Government Surveyor was requested to report whether a village reserve should also be incorporated. A design was submitted in 1852 for the proposed, but unnamed, reserve in the Parish of Byng, Bathurst County. Two years later, the first village allotments were measured for sale to interested buyers. It would appear that the village reserve first became known as Byng during 1854; a name borrowed from the County at the time of survey.

The Parish took its name from Admiral John Byng, sent to relieve the British garrison of Fort St. Philip in Minorca; under siege by the French fleet. Failing in his mission, Byng returned to England to be court-martialled for disobeying orders to defeat the French. He was shot at Portsmouth in 1757, despite a public outcry. Britain's Prime Minister, Thomas Pelham-Holles, used Byng as a scapegoat to divert attention away from his Government's continual shortcomings. Byng became a popular hero in the eyes of the British who readily saw through the diversion.

Byng's village boundaries were established in the Government Gazette on December 5th 1881. On March 20th 1885, the village site was proclaimed with an eastern boundary of Lewis Ponds Creek and Sheep Station Creek to the west. From that date, the previous titles of Springfield, Carangarra, Cornish Town and the Cornish Settlement should have become obsolete. While the first three names mentioned have long since disappeared, Byng is still as equally well known as "The Cornish Settlement".

Another belated boost came on April 19th 1893, when the village site was proclaimed as Byng Goldfield. Despite a general decline in mining activities, gold and silver were still being brought to the surface with the copper that was being dug a little less actively.

At the end of last century, economics entered the mining picture, heralding the closing stages of an era that was rapidly dying. Many of Byng's transient miners then moved to other more easily worked locations, eventually taking up other occupations. Somehow or other, the proclaimed village of Byng just faded into obscurity and never really progressed past the plan lying on the Government Surveyor's drawing board.

Before The Pioneers

In 1823, Bathurst was still a military outpost and barracks on the western bank of the Macquarie River. There were areas for grain storage, a jail, a hospital and cottages for Government officials. Settlers relying on military protection built houses of sod and turf, with thatched roofs, on the eastern bank at Kelso.

In June 1823, John Maxwell was appointed Superintendent of Government Stock at Bathurst. He took charge of 2,670 head of horned cattle, 2,050 sheep, 63 horses and 62 convict stockmen and shepherds. Maxwell was to set up strategic stations beyond the areas permitted for settlement; supplying Bathurst and Wellington convicts and officials with meat. The first of these stations was at Frederick's Valley. The western extremity of the valley was 3 kilometres west of present-day Lucknow; its eastern boundary was at present-day Shadforth. Other stations followed at Kings Plains (Blayney), Kings Plains No 2 (Millthorpe), Black Rock, Queen Charlotte's Vale, White Rock, Princess Charlotte's Vale, Caloolah, George's Plains and Bell's River. For wages, Maxwell was to receive 5% increase of all Government stock west of the Blue Mountains.

But aboriginals held the white intruders responsible for driving away kangaroos and opossums. They retaliated by attacking cattle for a substitute diet. Two stockmen working for the Reverend Samuel Marsden were murdered in 1823, near Guyong. G. T. Palmer also had his stock station at Guyong and one of his men, Charley Booth, was nearly shot in a native affray. By November, Judge Wylde reported that aboriginals had killed cattle, attacked Charley Booth and speared another worker. Wylde handed in his special ticket of occupancy and abandoned the station. Governor Brisbane declared a state of martial law in 1824 and numerous natives were hunted like animals and shot for bounty payments.

By 1829, the problem no longer existed and areas west of the Macquarie were thrown open to settlers. A Cornishman, William Tom Senior, was one of the first to take advantage of the situation. Tom hoped to find a far more suitable grant than he had chosen twice before at Tarana. A fellow-countryman, George Hawke, accompanied him; hoping for a better deal after one luckless year in the colony.

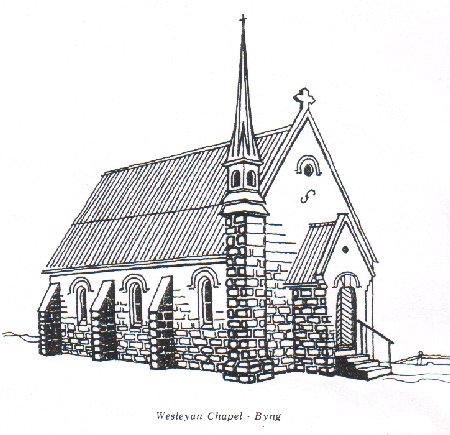

Byng Wesleyan Chapel

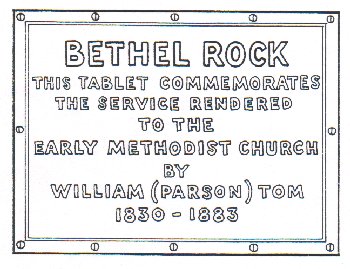

When the God-fearing Cornish pioneers came to Byng they worshipped on top of a ridge at Bethel Rock. This served as a pulpit on which William Tom Senior stood, with a Bible in his hand, to address the small but faithful gathering. Tom was a lay-preacher and Byng's first settler; having been granted 640 acres in 1830. This grant became known as "Springfield." After completion of his original five room lath and plaster dwelling, the outside services were transferred to Tom's home, pending construction of something more worthy in which to worship.

By 1842, a small rubble constructed building was officially opened. It was situated immediately below Bethel Rock, where religion had been founded in the valley. This became the first Wesleyan Chapel west of Bathurst and the second west of the Blue Mountains; a fact that greatly pleased the righteous Cornish folk who struggled to complete it.

A few foundations of the original church still remain; the site marked by a suitable memorial. Many of its stones were removed to be incorporated into the present-day chapel which opened in 1873. This is a quaint sandstone structure with a fading red-tipped spire and steeply raked roof with fretwork eaves. Although there are numerous other disused churches lying dormant throughout New South Wales, none seems to exude the inexplicable magnetism that emanates from the Byng Wesleyan Chapel.

Perhaps it is the solitary setting on a hill, silhouetted against a backdrop of huge evergreens foreign to our shores. Maybe it is the fine craftsmanship and originality of the mason who dressed the stone and created the design over 100 years ago. It could even be the imagination of the curious who stand, trying to recreate a visual picture of Byng's past; searching the building for a thousand answers that were thought to no longer exist.

Once, proud groups of settlers and their families walked to church along Byng's misty, hawthorn-lined laneways. They were fashionably dressed in warm clothing to brave the icy winds that prevailed for a greater portion of the year. Accompanying them were "assigned" servants who, no doubt, offered prayers of thanks to their TRUE Master and for their moments of reprieve under the charge of Christian gentlemen. On wet Sundays, settlers fortunate enough to own a cart or horse were excused for being conveyed to pay homage, rather than making that extra personal sacrifice to walk the distance. Arriving in such a manner on a fine Sunday morning was certainly unthinkable; a complete mark of disrespect for the Sabbath.

Still painted on the wall behind the pulpit of Byng's chapel are the words: "Worship The Lord In The Beauty Of Holiness." Now the message is cracked and peeling. The church steeple has been boarded up and the bell taken away. Its early morning message no longer peals throughout the valley to remind settlers, pioneers and copper miners that all should be forgotten for a day of rest. Dust and memories are the only regular gathering within the church today. The chapel is still the focal point of the valley, perhaps symbolising that man may come and go, but there will always be the Church.

Parson William Tom

1791 - 1883

Parson William Tom Senior was probably Byng's most notable pioneer. He was well-built, broad-shouldered and five feet eleven inches tall. His face was filled with character, conveying a warmth and kindness to those who also considered God to be their best friend. Tom was afraid of nothing and nobody, for he was armed with a sure protection that carried him through the toughest of situations. While others carried guns and weapons, Tom carried nothing but a Bible.

Unrepentant sinners found his manner to be stern and unforgiving. Fellow-businessmen regarded him as an astute opponent with an unblemished integrity. His family found him courageous and willing to face any challenge. Tom frequently spoke using quotations from the Bible that suited many of the situations that confronted him. He held reverence for three things. The first was God. The second was for John Wesley, founder of the Wesleyan Religion. The third was for Cornwall.

Circuit preaching and business trips often took Parson Tom off the beaten track and into the face of danger. One night he stayed at a public house but a lack of beds saw him placed on a couch in the hallway. Around midnight, Tom awoke to find several bushrangers taking advantage of the darkness to rob the guests and premises. One hit him over the head with a pistol butt, knocking him into a state of semiconsciousness. All valuables were then taken from the lay-preacher's clothing.

When one of the robbers struck a match to count the loot, he was horrified to recognise his luckless victim. A dazed Parson Tom overheard the bandits whisper his name. Then he felt the money and valuables being replaced into his pockets. When the cleric regained consciousness, he found himself neatly replaced and tucked in on the couch. A huge lump on his head convinced him that he had not been dreaming. Perhaps it was a sign that Parson Tom's efforts of preaching on the Bathurst circuit were starting to pay dividends: - in a painful kind of way!

From 1843, drought and trade stagnation caused many of Bathurst's settlers to sell starving stock for 5/- per head to the boiling-down works. Sheep had a value of only 6d. The Tom family took their cattle overland to Gippsland, in Victoria, setting up stations along the lonely way. John, Nicholas and James Tom sold their father's cattle at Port Phillip for eight guineas per head. The three brothers were amongst the first to attempt such a daring task. Over the next ten years, the Tom family became established in this way before copper mining reduced their profits.

Parson Tom owned many stations in the Lachlan area in partnership with his sons. There was Wilga, Tom and Bill, Huntawong, Gunningbland, Tom's Lake, Belangaramble, Booligal and Cowl Cowl. In later years, the Toms' cattle overlanding operations extended to South Australia and Tasmania.

Parson Tom's wife, Ann, possessed a beautiful singing voice and a good ear for music. This contrasted sharply with her husband, who had no idea of a tune or keeping in time with music. During worship in the Byng church, Ann Tom would frequently stop her husband, who was usually half a verse ahead of his congregation. In those days, church services lasted well over one hour and Parson Tom never wasted a minute. His sermons were delivered slowly and clearly, so that listeners understood the full meaning of the text. Perhaps the lay-preacher's rapid singing merely communicated his eagerness to impart God's word to his faithful congregation?

By 1880, Tom was so enthusiastic about Wesleyan Missionary work in South Africa, that he decided to lecture on the subject in Byng Chapel. A large map was prepared which SHOULD have made the narrative easy to follow. For the first time in his life, William Tom Senior was forced to admit that he had met a challenge he could not overcome. Poor illumination of the church was blamed for his inability to continue. Nobody wished to tell the distressed preacher that his highly troublesome African map had been hanging upside down.

The whole Bathurst district knew and loved the white haired preacher who came rain, hail or shine. In earlier years he had ridden an elegant grey mare to the numerous places where he conducted services. In later years he travelled in a sulky drawn by a less spirited pony.

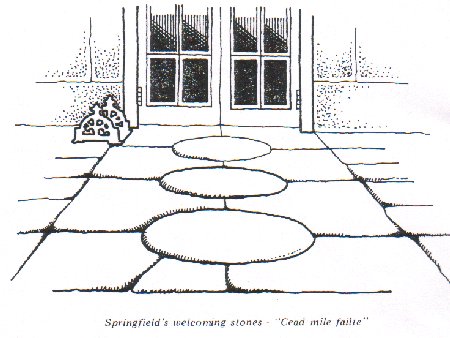

SPRINGFIELD

Parson William Tom's original wattle and daub dwelling disappeared a long time ago, joining many of Byng's pioneer buildings that were of a more temporary nature. New Springfield became the replacement home for the Tom family in 1847. The two-storey Georgian-Colonial mansion was completed by 1854; its thick stone walls ensuring that little structural attention has ever been necessary.

Springfield is an imposing sight to behold. It has a full length front verandah and awning, supported by several white pillars. Set high on a hill overlooking Sheep Station Creek, a colourful collection of English trees and shrubs now highlight the spacious grounds and landscaped gardens that await each Autumn's kaleidoscopic magic.

Parson Tom is unlikely to have considered Springfield to be a mansion. He probably felt it was merely an improved dwelling in which to house his wife and thirteen children. Fellow-countrymen, newcomers to Byng or Christian travellers passing through the district were undoubtedly impressed by Tom's humble and self-denying attitude. Guests and visitors alike were greeted by three stones set into the front verandah's paving. They were inscribed: "Cead mile failte" - Celtic for "One Hundred Thousand Welcomes".

It wasn't necessary to understand the Celtic language to feel the warmth of Springfield's welcome during a drawn out icy winter evening. Most of the exploration leading to Australia's gold discovery commenced from Springfield. Members of the Tom family located the first PAYABLE gold and handed it over to Edward Hammond Hargraves for Government consideration. Perhaps Hargraves took the greeting on Springfield's front verandah too literally, when he claimed for himself the Government's reward? Could this now be the reason why Byng leads a sheltered life of anonymity; casting a suspicious eye on all strangers who stumble on or visit the Cornish Settlement?

George Hawke

1802 - 1882Byng's variety of English trees and colourful hawthorn bushes were brought to the valley by George Hawke, another of the Wesleyan foundation settlers. Hawke was a native of the Cornish coastal village of Bedruthan. Standing only five feet six inches tall, his slight build was attributed to many sicknesses that he had suffered prior to emigrating to the colony. Hawke became noted for his over-cautious speculations, lacking confidence rather than hard work or initiative.

Hawke's first employment at the Cornish Settlement was under a 3 year agreement with Parson Tom; educating his ever growing number of children. Hawke was to receive five pounds and five cows after one year's service. At the completion of two years, he was to be given three pounds and five cows. The same arrangement applied for the third year, with a 6 acre parcel of Tom's land, (enclosed by a three rail fence), being added as final payment. Tom was to plough this land twice and then sow it with good quality wheat. Hawke also received free board, cooking and washing in exchange for the products of his fourteen cows, but he retained the right to remove them at any time. Either party could terminate the agreement after 3 months' notice. Due to the absence of ready cash, such arrangements were usual for the period.

When Hawke purchased his own land, he and Tom applied for convict servants to help clear timber and dig up tree roots in preparation for considerable cultivation of crops. Each week, convicts were to be supplied with 10 pounds of flour, 7 pounds of salted-down beef or 4 pounds of pork. Each year, they were to be given 3 striped cotton shirts, 2 pairs of trousers and 3 pairs of boots. If a convict was well-behaved and worked hard, he might be given three extra pounds of beef, one pound of sugar and a little milk as a bonus. Troublesome men could be taken before a Magistrate and flogged for disobeying orders or refusing to work. Others could be placed in solitary confinement, (on a bread and water diet), or even sentenced to a month in irons on a chain gang.

Fortunately, Tom and Hawke were more than pleased with the co-operation by their men, whom they preferred to call "assigned servants," rather than "convicts". These helpers worked with little supervision. They soon learnt to appreciate that there was a higher Authority than a Magistrate; an Authority who had long before created all men equal and forgiven them for their sins.

Hawke paid his man a small weekly bonus so that he might have something to fall back on when his sentence was completed. George once came within three inches of being crushed to death when a pile of sawn timber collapsed. His helper shouted a warning at the crucial moment, saving Hawke's life.

The Cornishman's arms and legs were severely bruised and swollen and the district's only doctor was based at Bathurst's Government Hospital. This made travelling such a long and painful distance impracticable.

After returning to Cornwall to marry, Hawke arrived back in Sydney during 1838. With him came 2,000 assorted trees and shrubs in packing cases lined with straw. It took six weeks to transport them over the mountains by bullock dray. Few survived the ordeal of being shipped halfway around the world to be planted in the midst of Australia's most severe drought to that date. There were elms, ashes, oaks, sycamore pines, poplars, beeches and cypresses and they no doubt conjured up many happy memories for the valley settlers.

Acting on their own initiative, the people of the Cornish Settlement met at Springfield to pray for relief from the drought. They were promptly blessed with rain that fell ONLY within a 10 kilometre radius of the Settlement. It was not until the whole colony participated in a Government proclaimed day of prayer that rain generally fell to ease the situation. Years later, George Hawke recalled in his diary: "On several occasions in time of drought, rain has come on the very day. Who will presume to say that God does not hear and answer his people when they humble themselves and ask favours of Him?"

It is ironical that Hawke's descendants are the only people to retain their original holding at the Cornish Settlement. This can be attributed to Hawke's perseverance and rationalism during a period of general madness amongst the inspired prospecting and mining population. George Hawke's excellent anticipation saw him open a store to supply Byng's copper miners with meat and provisions and another at Ophir until the rush ended. Tried and proven commodities helped make George Hawke Byng's most calculating businessman.

In his diary, the little Cornishman sometimes recalled projects in which he considered he had failed or could have done better. Even if George Hawke sometimes considered himself a failure, nobody would dare deny that he was Byng's most successful one.

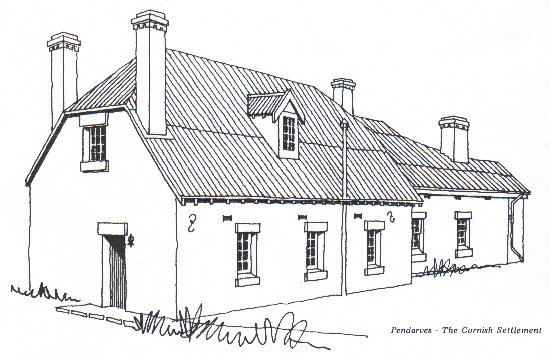

PENDARVES

Pendarves, in the Cornish language, means "at the end of the oaks," an appropriate name and description for the homestead commenced by George Hawke during 1850. Originally, the entrance was along a lengthy driveway lined on either side by huge, sentinel-like oak trees. The driveway still exists but now the gate is locked; the oaks meeting overhead to form a tunnel or guard-of-honour to the man who founded the orchard industry in Orange.

Hawke introduced cherry, plum and apple trees to Pendarves Farm during 1841. His first crop consisted of two apples. By the following year, 26 apples had grown; a disappointing experience to anybody but a Cornishman. Today, the Orange district is predominantly reliant on orchard produce, perfectly suited to its brisk climate.

Sited to the west and high above the Cornish Settlement, Pendarves commands a magnificent view extending many kilometres to the east. It is a two-storey, red brick building with a high sloping roof, featuring two distinguished chimneys at one end. Adjoining the original construction are sandstone extensions, completed around 1890.

Byng's hawthorn bushes were also introduced by Hawke as inpenetrable fences to keep stock and poultry within their province and unwanted predators without. In later years, Hawke sold hawthorn cuttings to other settlers for ten pounds per thousand. Now they can be seen over a 30 kilometre radius of the Cornish Settlement. Every orchard tree and hawthorn bush represents George Hawke's longlasting trademark throughout the area.

John Glasson

1803 -1890

John Glasson reached Sydney Town during April 1830; emigrating from the Cornish village of Breage. Glasson was strongly built and five feet eleven inches tall. He was a strict Methodist, supporting Parson Tom in the belief that only Wesleyans would get to Heaven. Glasson's calm manner and sincerity quickly gained the respect of all that met him. He was also a calculating, but honest, businessman who seldom made a decision without first referring to a Higher Authority.

In 1832, Glasson and Hawke became partners in dairying. Hawke bought 320 acres of Glasson's "Newton Vale" property for sixty-five pounds; renaming it "Pendarves Farm." Half of the purchase- price was paid for with Hawke's cows and their calves by the coming Spring. The balance was repayable to Glasson over three years: - Free of interest! Hawke paid one third of Glasson's dairy expenses in exchange for one third of the profits. The same arrangement applied to the hogs belonging to Glasson. It was to be a long and co-operative partnership extending over 25 years. During that time, the two never had a cross word or difference of opinion.

The Reverend Joseph Orton visited the Cornish Settlement to preach in 1832. Orton was Chairman of all Methodist circuits in New South Wales. The Church Leader was deeply touched by the sincerity of John Glasson, William Tom Senior and George Hawke. It was their desire to build a local chapel in which to share their beliefs with others. All felt that, in the continually expanding frontiers, there were too many people without adequate religious representation. Glasson quickly donated a suitable tract of his land for the proposed chapel at the Cornish Settlement. This gesture would save the Wesleyan Mission Society from providing funds that could be put to far better use in Bathurst, amidst the heart of unprecedented crime and violence.

But it wasn't always necessary to travel to Bathurst to sample crime and violence. One morning, in April 1844, Glasson awoke to the sound of an unusual noise. Creeping to the outside of his home, he saw a stranger exit from another door. Glasson collared the intruder, only to find that he was no match for his huge opponent. The Cornishman picked up a garden hoe in defence, swinging it wildly and hitting the intruder hard on his back between the shoulder blades. The man was identified next morning and charged with breaking and entering with intent to steal. Because of the defendant's previous good record, Bathurst Court imposed a light sentence: 3 years in irons on a road gang!

In 1857, Glasson, his wife and a son emigrated to Papakura, New Zealand. Glasson's wife had long suffered from asthma and the change of climate prolonged her ailing life a further four years. Glasson's "Linwood Estate" consisted of 900 acres on which he grazed sheep and bullocks. One of New Zealand's first exotic timber mills was built to handle eucalyptus trees grown by the Glassons for fencing and construction.

BOOKANAN

John Glasson's 640 acre grant was approved on 1st November 1830. By the following year, British Regulations stopped land grants to settlers with resources. Crown Land then sold for a minimum of 5/- per acre to discourage unsuitable settlers. Unproductive people in this category found that the Government took back their grant. It is debatable whether Glasson was successful in his first short year of operation. He was more than satisfied to show a one pound profit from his first wool clip. During his second season, profit increased to 27/6d.

Glasson's first home was of wattle and daub construction and he named it "Newton". During 1842, "Bookanan" became its replacement; a small building assembled from rough undressed rubble covered with creamish plaster. Before long, a separate portion was built nearby. By 1849, a two-storey Georgian style construction linked the earlier stages to form a "U" shaped dwelling. Each of Bookanan's three chimneys marks an independent development to Byng's longest standing structure.

By September 1834, Newton Vale had 20 acres of wheat growing and another 10 ready for the plough. Turnips and potatoes filled one paddock and the milking yards were fenced. There was a stone milking hut with a thatched roof and two others for storage of crops and equipment. When a wheat blight attacked the crops of the Cornish in 1835, Glasson and Hawke developed a side-line for financial survival. The district's leading men were more than anxious to buy gallons of the fine liquor being brewed by the duo. Ale sold in Bathurst for 2/- per gallon and beer for 1/6d. In anticipation of better times, Glasson bought portion 34 of Anson Parish in 1839. It was 640 acres adjoining Bookanan's southern boundary. But "better" times were to prove few and far between.

In October 1844, Lewis Ponds Creek and Sheep Station Creek flooded after 10 days of heavy rain. Streams of water gushed through Bookanan and its yard was littered with broken fences, trees and logs. Glasson and Hawke lost 500 lambs through the deluge. They were left with only 2,900 sheep and 450 lambs to divide. Both had been speculating by purchasing stock at greatly reduced prices from owners who did not wish to have them boiled-down into tallow for candles.

John Glasson's pipe-dreams of becoming a copper magnate collapsed a long time ago; like the walls of his Carangarra smelter and payhouse that stood alongside his homestead. Gone are the wagons and teams loaded with ore that once rumbled past Bookanan; vibrating its stuccoed walls and foundations. Bookanan's walls still quiver occasionally; usually when a stranger passes nearby. It is the unknown that Byng fears! Strangers have imposed on her hospitality far too often.

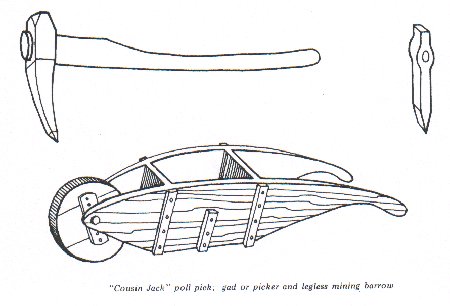

The Cornish "Cousin Jack" Miners

Copper was discovered in New South Wales during 1845 at Molong and Lipscombe Pools Creek, 10 kilometres east of Canowindra. There was another strike in 1846 near Rockley, south of Bathurst. The public was more than aware of the copper industry and its profitability, after continually reading newspaper reports from South Australia's rich Kapunda, Glen Osmond and Burra Burra mines.

Beside Byng's church is Sheep Station Creek, which flows a short distance north to meet Lewis Ponds Creek. During the early 1850's, Sheep Station Creek was dammed to conserve water for hundreds of Cornish copper miners who pitched their tents or built crude bark huts along its banks. They were known the world over as "Cousin Jacks", a title explaining the close-knit relationship existing between members of the race.

The Cornish were generally poor but humble folk, who shared a dedication to hard work, ingenuity and an unblemished integrity. If a local employment opportunity arose, there would always be a fellow-countryman known who would emigrate to fill the position. The other advantage was that the newly imported worker and his employer probably understood each other during conversation.

The Celtic dialect spoken was a fractured off-shoot of the English language with thick traces of Irish, Welsh and Manx accent. One could expect something like: "Summat funny 'bout Cornish lanwage. That be fac'. S'pose un'll do. Be pr chillun I be worried 'bout, tryin' t unnerstan' ee, Mawther."

Translated into the English language, it probably meant: "There's something funny about the Cornish language. That's a fact. I suppose it'll do. It's the poor children I'm worried about, trying to understand you, Mother." The Cornish were also noted for their fine sense of humour!

The "Cousin Jack" miners wore flannel shirts and thick boots in their damp subterranean areas they called "stopes". A paper mache helmet offered little head protection. Melted to its front was a tallow candle which provided a dim and flickering light under which they worked. Low wages were not a great reward for toiling under suffocating, dusty conditions that could lead to a greatly reduced life span through heart and lung diseases.

Access to the mines was by a series of ladders leading to the various "levels" or "galleries." All Cousin Jacks worked under the direction of a "Mining Captain." This prestigious title was bestowed on the most experienced man who had proven his abilities through hard work and continued profitable results. He was usually made a share-holder in the company, supervising every function of the mines. It was each Cousin Jack's ambition to one day have the title of "Mining Captain" prefixing his name as a mark of respect and accomplishment.

In January 1849, Glasson's brother-in-law noticed copper deposits near Sheep Station Creek. They were traced from Bookanan into Richard Lane's adjoining property. Within four months, Glasson and Lane decided to develop Byng's copper resources, despite discouraging news that the proprietors of the Molong mines were experiencing heavy losses through a virtually useless blast furnace that had proven unsuitable.

Byng's Early Copper Mining Era

By August 1849, Glasson and Lane employed a "Mining Captain" for six months to oversee half a dozen men digging on their properties. The miners paid their own expenses; being credited with goods until the ore was marketed. They would receive 12/- in the pound from Glasson and 10/- from Lane.

By May 1850, Glasson's Carangarra shaft was already deeper than the level of Sheep Station Creek and drought conditions made pumping operations unnecessary. He and Lane entered into a financial agreement to build a smelter to convert the 140 tons of ore already extracted. Three months later, discouraging news was received regarding the closure of the Molong and Rockley mines, through their imperfect smelters. But Glasson and Lane continued to employ a workforce of six and eleven men respectively.

These miners were now on the tribute (commission) system which varied from 6 to 10 tons of ore in every 20 they dug. Over 200 tons of rich ore stood awaiting the proposed smelter. The copper industry had been kind to the Cornish duo, presenting them with only ONE special problem. There were now 200 people living and working at the Cornish Settlement and the Wesleyan Chapel would have to be rebuilt or extended to hold the capacity crowds that flocked there every Sunday morning.

Lane's four shafts were named after his original miners; Jenkins, Tucker, Rowe and Weeks. The Jenkins shaft was now 90 feet deep and, two thirds the way down, a tunnel had been driven northwards to connect with Tucker's shaft; a 60 foot excavation. Tucker's shaft provided a rich cross lode of ore measuring 22 feet in width. Rowe's shaft was only 21 feet below the surface but its lode was 13 feet wide. To discourage numerous take-over offers, Lane openly stated that he would not take fifty thousand pounds for his land.

Glasson felt confident that his single Carangarra shaft of 126 feet would yield at least another 1,000 tons of ore. Even his children, Johnny and Bobby, were digging a new spur with a minimum of effort. They soon brought a quarter of a ton of rich grey ore to the surface and there were several more spurs yet to be explored and opened.

Before smelting, the ore was broken into small pieces and left in moulds open to the air. This process was called "calcination." It destroyed the arsenic, sulphur and antimony content; harmful to the production of high quality copper ingots.

Next to Glasson's calcinating yards stood two adjacent blast furnaces. They were built from local soapstone, under the direction of a supposedly expert consultant employed by the Cornish duo. A strong wooden platform surrounded the furnaces, about two foot from the top. Calcinated ore was wheeled onto this platform and a suitable flux added, before being tipped into the furnace. During the roasting process, slag or residue was expelled by ducts at the front of the ovens. After processing, the 40 pound ingots (in moulds) were quickly submerged in water to prevent oxidisation. Adjoining the smelters was a payhouse, used to assay three samples of each miner's work for content. One sample was retained by the Mining Captain, another by the employer and a third by the miner.

The smelter's blast came from a small brick engine house containing a motor driven by a Cornish boiler. The engine could maintain 1,200 revolutions per minute effortlessly. An eccentric fan, 3 1/2 feet in diameter, forced air into the ovens through brick drains that passed beneath.

Glasson and Lane then employed a fireman, two smelters and five others to stoke up the fire with charcoal. Constant thumping sounds echoed throughout the valley as smoke belched from the Cornish boiler to impurify the virgin air. People cared little of these inconveniences with a promise of regular employment during an extended period of trade stagnation. Initially, it was planned that the furnaces would be used on an alternating basis during daylight hours only. Daily produce was expected to be 3 to 4 tons of ingots.

At the first attempt of smelting, the furnace was unable to bear the blast and it wasted more copper than it produced. Two tons of ingots resulted but two and a half tons escaped through the waste chute with the slag. Even after calcination, the highly sulphurous ores were unsuitable for the blast furnace. "Expert" opinion had failed to reveal that a draught furnace would have been far more practical.

Byng's first 132 copper ingots were paraded through the streets of Bathurst on a dray. They were the first to be displayed at that locality. Perhaps this was an enticement for local investors to now support the ailing scheme. Despite the unprofitable wastage, Byng's large quantities of red and black ores still provided ingots of almost pure copper.

During November 1850, the Committee of Australian Society announced that it would award the Governor FitzRoy Medal to the person(s) who prepared, for export, the largest quantity of metal extracts from their ore by the first Tuesday of May 1851. Glasson and Lane felt confident of winning the award when their ingots were auctioned in Sydney for one hundred and fifty pounds. This was 5/- per ton more than that being mined at the rich Burra Burra Mines in South Australia.

Glasson quickly sold 34 tons of untreated ore to an anxious buyer for three hundred and twenty-seven pounds. He and Lane then considered sending the remainder to Swansea, in Wales, and leasing their properties to the unlimited finance of a big company. After paying their miners' tribute, the two Cornishmen would each be five hundred pounds out-of-pocket for the engine and useless smelter. But the Cornish sense of humour still shone through. Glasson and Lanestill owned 2 horsepower each of the district's most expensive 4 horsepower engine!

Samuel Stutchbury, the Government Geologist, inspected Glasson's Carangarra mine on April 12th 1851. He was impressed and reported large lodes in three shafts already above tunnel level. Stutchbury was unaware that at that very moment, two local youths were busily occupied some 7 kilometres away at Guyong, weighing Australia's first samples of PAYABLE gold. They had been discovered a few days earlier at a spot destined to become known as Ophir. Soon, Carangarra and Byng would come to a standstill when miners replaced their picks and shovels with gold pans and cradles.

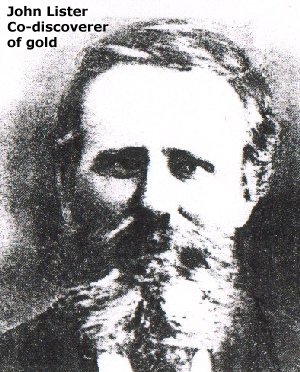

Discovery Of Australia's First Payable Goldfield

During February 1851, Edward Hammond Hargraves passed through the neighbouring Guyong area, on his way to Wellington to search for colonial gold. Noticing some promising quartz samples at Lister's Guyong Inn, he formed a prospecting partnership with John Lister, James Tom and William Tom Junior. At Springfield, William Tom Junior built Australia's first gold cradle to Hargraves' specifications. The trio were given cradling lessons at the junction of Sheep Station and Lewis Ponds Creeks. Hargraves' part in the actual discovery of PAYABLE gold was now completed.

Displaying his ignorance of prospecting procedures, Hargraves merely washed the top layer of river gravel, obtaining very few "colours" which were almost invisible to the naked eye. The small traces of alluvial gold were enough to attest its presence, but insufficient to pay for its extraction.

Hargraves announced to his partners that he intended travelling to Moreton Bay (Brisbane), to further pursue his quest or that he might even return to the Californian goldfields. Long after he had given up in disgust, John Lister and William Tom Junior found golden nuggets weighing 4 ounces and cradled a fine ounce of gold at the spot soon to become known as Ophir. Using their own initiative, the two dug well down below the surface to find PAYABLE gold at a spot Hargraves had previously declared unsuitable. Tom and Lister delivered the specimens to Hargraves, so that he might petition the Government for a reward for the foursome.

Hargraves became endowed with the title of "Australia's First Discoverer of Gold"; being paid a sizeable reward and receiving a high-ranking Government appointment with gratuities. Somehow, he neglected to even mention the three other trusting members of his partnership; later denying that such an arrangement ever existed. The Tom brothers and Lister spent the rest of their lives petitioning the Government to gain reward and recognition for the title that was rightfully theirs.

Now masses of unchecked blackberry bushes, growing beside Byng's church, try to smother Sheep Station Creek into oblivion, as it too struggles for last minute recognition as the place where the whole disappointing adventure started.

Byng's Era Of Company Mining

On June 27th 1854, a petition was presented to Parliament begging that the Carangarra Copper Mining Company be granted a certificate of incorporation. The petitioners were George Allen, John Alexander, John Fairfax, Samuel Hebblewhite and David Jones; Directors and Proprietors of the proposed company. The Carangarra Copper Mining Company had been established in Sydney during April 1853 with fifty thousand pounds capital; namely 10,000 shares at five pounds each. Provisions existed for dissolution if loss at any time equalled one third of the subscribed capital. Carangarra Estate now held a 21 year lease on two 320 acre properties and another of 156 acres belonging to Glasson and Lane. The former owners were to receive 10% commission of all profits. Perhaps the fifty thousand pounds capital might see Byng flourish and bring the fame that she had been deprived of when Glasson and Lane's one thousand pound venture had innocently failed.

Byng again thrived on expectations, promises and the speculations of newcomers to her down-trodden realms. The Carangarra Copper Mining Company proudly exhibited Byng's ore in the Paris Exhibition, held in Sydney during 1855. But after Australia's gold discovery, there was something about strangersand promises that Byng had learnt to thoroughly distrust.

By 1875, the Carangarra Company grossed 784 tons of copper ingots from 5,600 tons of Byng's ore. A three inch lode at the thirty foot mark increased to twelve inches at the one hundred and eighty foot level. At two hundred and forty feet, it became eighteen inches wide. Twenty-five years earlier, two of Lane's shafts had provided miners with lodes of twenty-two and thirteen feet in width - at a mere sixty and twenty-one feet respectively. But since 1851, Byng was filled with uncertainty and the harsh reality of an outside world filled with exploitation.

In 1881, the Government Geologist, C. S. Wilkinson, visited Carangarra's idle shafts, expressing an opinion that they would prove auriferous. He was more astute than Samuel Stutchbury, the Government Geologist who visited Carangarra on April 12th 1851. Stutchbury had completely overlooked such a possibility and once again, a stranger had deprived Byng of the merit worthy of her obliging nature.

Gold and silver were regularly brought to the surface with copper ore by 1886. Gold tributing continued in Carangarra's old shaft until another idle period in 1891. An adit from the main lode now stretched one thousand and fifty feet to a vertical shaft driven a further two hundred feet below. Then came a mining revival and another stoppage of work in 1898. Within two years, Parker's Gold and Copperfields Syndicate repaired Carangarra's vertical shaft, sinking another two hundred and fourteen feet to put out a cross-cut to meet the lodes.

In 1895, while Byng watched Carangarra's seesawing escapades with a sceptical eye, the Whitney Green Gold Mining Company obtained 525 ounces of gold from 164 tons of ore. The company sold this gold for one thousand, eight hundred and sixty-eight pounds. The ore was crushed in a six-headed battery stamper standing by Lewis Ponds Creek. But Lewis Ponds Creek also had an aversion to exploitation and its waters created untold seepage problems for the mine.

The Whitney Green Mining Company became the subject of litigation in 1896. By the following year, the Springfield Pastoral Estate Co. Ltd took over operations. It planned many improvements. There would be a private township laid out for local people and Cousin Jacks. But Byng's village site had been surveyed in 1852 and its boundaries notified in the Government Gazette during 1881. The site had also been proclaimed as Byng Goldfield in 1893 in a belated attempt to atone numerous oversights and false promises. After 45 years, Byng was still no more than a village represented by paper and ink on the Government Surveyor's drawing board.

The Springfield Pastoral Estate Co. Ltd also owned and operated the Mount Nicholas copper mines nearby. Between 1888 and 1890, several of its shafts were between one hundred and two hundred feet deep. During this period, an onsite smelter proved unsuccessful and the ore was sent by rail to Lithgow for smelting. The same circumstances applied to the Mount Bulga copper mines.

The Springfield Pastoral Estate Co. Ltd reopened Mount Fraser's mines in 1907. The one hundred foot shaft provided a lode varying between eight and twenty-four inches. Fifty tons of copper ore sold for six hundred pounds. Better days had seen sixty Cousin Jacks actively employed. Again, an ineffective smelter led to the ore being sent to Lithgow.

The Old Ophir Lead, Icely, Brittania, Big Bell and Little Bell copper mines commenced operations around 1850. Copper from the Old Ophir Lead was smelted at Brown's Creek. Ore from the Icely mines was initially smelted at Byng, until an on-site smelter was erected. This then treated the produce from theBrittania, Big Bell and Little Bell mines. During 1877, both smelters polluted Byng's virgin air for the last time.

Byng and Lewis Ponds Creek no longer play host to the Belmore, Moonta, Nelson, Gurophian, East Block and Dolarmite mines, which also functioned over a sixty year period. In 1872, the Great Western Copper Mining Company floated many of these concerns as public companies. Towards the end of the era, most of the ore was sent to the English and Australian Smelting Company at Waratah, Newcastle.

Even Byng's asbestos and kaolin deposits now lie undisturbed. Kaolin is the white clay used as a base for porcelain and china. Byng has been a constant provider for all who have believed in her for the past 150 years. Now Byng leads a sheltered life of anonymity, casting a suspicious eye on all strangers who stumble on or visit the Cornish Settlement.

Gone are the "Cousin Jacks" who once scampered from their crude dwellings across paddocks covered with early morning dew. Carangarra and her filled-in shafts still cover the hillside like a giant rabbit warren, but where are the rabbit-like Cornish miners who once scurried around these shafts and galleries?

And whatever happened to the humble Cornish folk that walked Byng's misty hawthorn-lined laneways each and every Sunday morning? The Wesleyan Chapel sits forlornly listening to the babbling waters of Sheep Station Creek nearby. It has been a long and patient wait for a new lease of life and usefulness.

Legend

- Byng Village Reserve - Surveyed 1852

- Present Byng Wesleyan Chapel - Opened 1873

- Byng Pioneer Cemetery

- Bookanan - Home of John Glasson

- Carangarra Smelter & Payhouse Sites

- Original Byng Church Site & Memorial - 1842 to 1873

- Bethel Rock - First outdoor Church Services held here in 1829

- Lewis Ponds Creek - Named after Richard Lewis, a member of Surveyor Evan's party when area first explored in 1813

- Private Road

- Site of Joseph Glasson's "Cottage of Content"

- Carangarra Mines

- "Willow Cottage"

- Sheep Station or Back Creek

- West Guyong Methodist Church

- East Guyong School

- East Guyong Church and Cemetery

- Diamond Hill Mine Site

- Luck's Hill - Named after Publican George Luck who took out the original licence for Lister's Wellington Inn. Bathurst - Wellington mail coached robbed here on June 27th 1849. On August 23rd 1850, Richard Glasson and Henry Peffler also robbed

- Pendarves - Originally half of Glasson's Grant

- Site of Guyong Blacksmith's Shop

- Old Guyong Post Office Site

- Methodist Church Site - Circa 1857

- Kyongs or Wellington Inn from 1838. Attacked by bushrangers in November 1839 and Publican Luck's wife shot dead. Hargraves visited here on February 10th 1851, on his way to Wellington to find a goldfield.

- Guyong Estate - Originally G T Palmer's centre station (prior to 1829) on Ticket of Occupancy. Granted to William Richardson who sold it to Surveyor John Nicholson in 1835.

- Richard Lane's Mine Sites

- Original Springfield Site - Stone quarried here for Byng's two Churches, Bookanan and New Springfield

- New Springfield - Commenced 1847

- Knob Copper Mine

- Hawks Nest Copper Mine (approximate location)

- Thunder Castle Copper Mine (approximate location)

- Oaky Smith Copper Mine (approximate location)

- Rat's Castle Copper Mine and Chinaman's Hill

- Whitney Green Copper and Gold Mine

- Quartz Hill - 3058 feet

- "Quinton"

- Godolphin and Cockatoo Hill

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

COPYRIGHT 1978 by John Rule & Liina Truu.

National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0-9595902-0-X

Printed by Mintis Pty. Ltd., (Rear) 417 Burwood Rd., Belmore, N.S.W Australia.

Additional copies of this book can be obtained from the Author, Post Office Box 112, Yagoona, N.S.W. 2199.

Two Dollars plus 45c postage should be included.

Also by the same author:

The Cradle of a Nation - release date November, 1978.

The true story of Australia's gold discovery at Ophir in 1851.