[Much of the information which follows and some of the photographs are extracted from Rob Bartlett's book "First Gold - Ophir N.S.W." published in 1999 (contact: newrecruits@ozemail.com.au). Though the ground has been worked over many times, this book is an excellent compendium of the main facts. Another good reference is John Rule's text in The Cradle of a Nation. - JCC 2003]

Background

For the first twenty-five years of European settlement in New South Wales, the Blue Mountains, part of the Great Dividing Range, blocked westward movement. Then, in 1813, Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson, by keeping to the ridges rather than the valleys, found a way across, opening the way to the western plains. Late in 1813, the Government's Assistant Surveyor Evans reached and named the Macquarie River (for the Governor) and described the area round present-day Byng. During six months of 1815, convict labour was used to construct a 163-kilometre road across the mountains, and a settlement was established at Bathurst. In 1817, John Oxley explored as far as the Wellington Valley, which he named for the Iron Duke, news of whose victory at Waterloo two years before must have only recently reached the colony.In 1823, Lieut. Simpson, guided by John Blackman, traced a road through to Wellington, and there established a settlement. The road ran from Guyong by Swallow Creek and thence across to Calcula country. The area of which Byng forms a part was originally known as Guyorog and later as the Sumerhill country, being later called Guyong (which was used as the mailing address as late as 1865). As early as 1836, enterprising pioneers like William Lane had acquired land in the area, and in 1839, Lane's brother-in-law, William Tom was granted 640 acres at the Cornish Settlement. Little is known about aboriginal resistance to these new arrivals.

Prologue

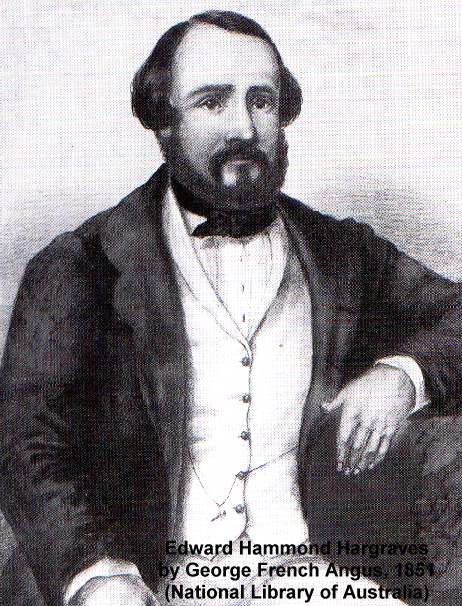

While Edward Hammond Hargraves is credited with the first discovery of gold at Ophir in February 1851, there had been many rumours of gold before this. It was undoubtedly these rumours that, in fact, led Hargraves to the site of his famous - and rather controversial - "find".Australia's first European gold discoverers appear to have been convicts working on the road over the Blue Mountains in 1814. Far from receiving a reward, they were flogged for their trouble, the government fearing a rebellion if these finds became generally known in the colony.

In ensuing years, further indications that gold was to be found in the colony's Central West were kept secret by successive Governors.

On 15 February 1823, Assistant Surveyor James McBrien noted in his fieldbook his findings of particles of gold in the Fish River between Rydal and Bathurst. That same year, a convict working on roads near Bathurst is also reputed to have found specks of gold.

In 1839, Polish-born explorer and geologist "Count" Paul Edmund Strzelecki (who discovered and named Mt. Kosciuszko) notified the government of his discovery of alluvial gold near Hartley in the Blue Mountains, and at Wellington. But the Governor, Sir George Gipps, "frightened me into saying nothing about it", the Pole claimed afterwards. However, when he returned to England, his rock samples went with him. These were examined by notable English geologist, Sir Roderick Murchison who, after seeing the samples, was convinced that "gold would be found in the Eastern Cordillera of Australia".

The Rev. William Branwhite Clark, an Anglican clergyman, noted geologist and friend of Murchison, sailed to Australia in 1839. In 1841, he found gold specks in quartz near Hartley and Bathurst, but Governor Gipps convinced him to remain silent on the subject. Clarke recalled years later that Gipps said "Put it away, Mr Clarke, or we will all have our throats cut". He would eventually be rewarded for his efforts, receiving £1000 in 1853, after a government enquiry into the management of the Australian goldfields, and £3000 in 1861, as "Scientific discoverer of gold in New South Wales".

There had also been numerous reports of discoveries by shepherds. In the 1840s, Hugh McGregor, a shepherd from the Wellington area, found gold at Mitchell's Creek. He travelled to Sydney by mailcoach with his gold specimens, which were exhibited in the window of M. Cohen's jeweller's shop in George Street.

William Tipple Smith, owner of a lapidary and jeweller's shop in George Street, Sydney, is also reputed to have found gold west of Bathurst. No doubt he was encouraged by the McGregor specimens exhibited in Cohen's shop which was very near his own business. In February 1848, Smith wrote to Sir Roderick Murchison, enclosing gold samples and an indication of their origin. Murchison contacted the Secretary of State, Earl Grey, informing him of the letter and suggesting a mineral survey of the region be carried out. Grey's decision, however, was negative, as he feared that a goldrush would have a dire effect on the colony's main financial resource, wool-growing. Smith persisted and finally met with the Colonial Secretary, Edward Deas Thomson, in January 1849, taking with him a 3½-ounce specimen of gold, the origin of which would only be disclosed upon payment of a reward. When Governor Fitzroy was shown the nugget and made aware of Smith's claims, the matter was dropped.

Before 1851, the area where Summer Hill and Lewis Ponds creeks converge was known as "Yorkey's Corner", after a shepherd called "Yorkey" who lived in a hut close by. "Yorkey", employed by William T. Trappitt, who owned land in the vicinity, was rumoured to have found a nugget near his hut. This was probably the same nugget that came into the possession of William Trappitt and may be the same one that had found its way into the hands of William Tipple Smith, although Smith claimed to have found the nugget himself. Rumours also suggest that Mr McDonald, a shepherd working for William Lane, and Mr Delaney, a shepherd working for Henry Perrier, found samples of gold at or near Yorkey's Corner. Although it is difficult to substantiate these rumours, it seems an undeniable fact that gold had been discovered in New South Wales before 1851 but was most probably unpayable. Even if the specimens were substantial enough to warrant further investigation, the government of that time preferred not to act and to keep the matter quiet.

In 1849, at Thomas Icely's property "Coombing Park" at Carcoar, the Belubula Copper Mining Company had discovered samples of gold. Two months after the find, the Colonial Secretary, Deas Thomson, was a guest of Mr Icely. It is highly likely that on this occasion he was shown these samples, which eventually ended up in England with Murchison. Sir Roderick was convinced that gold could be found west of the Great Dividing Range and as early as 1846 had encouraged the Cornish copper and tin miners migrating to the colony to search for gold in the region. His views went unheeded.

It appears that the main players in the early gold discoveries, Strzelecki, Clarke, Smith and Icely, all hoped that Sir Roderick would be the catalyst for an impending gold rush. But this role was to be played by another individual.

Hargraves

Edward Hammond Hargraves was born at Gosport, England in 1816 and at the age of 14 was employed as a cabin boy on board Captain John Lister's ship, the barque Wave. Lister's wife Susan and their infant son, John, were on board and Hargraves had become friendly with both, sometimes playing with the child. By 1832, when he was 16, Hargraves was on the ship Clementine, collecting beche-de-mer and tortoise shell from the Great Barrier Reef but after an outbreak of yellow fever, which killed 20 of the 27 on board, he returned to England. He was soon back in New South Wales, however, working for Captain Hector near Bathurst, a region he would well remember at a later date.

He had left Captain Hector's property by 1836 when he married Clara Mackie, a woman of some means, but by July 1849, after some unsuccessful business ventures, the ambitious Hargraves was back at sea. This time he was on board the Elizabeth Archer, bound for the newly found California goldfields, where he hoped to make his fortune. Hargraves, a huge man of 114 kilograms, found the work in California tough. However, he learnt the techniques of the gold pan and cradle as well as other useful information from his friends Enoch William Rudder, a metallurgist, and Simpson Davison, an experienced miner. Rudder had travelled to California with his two sons, Augustus and Julius, hoping to promote a gold-washing machine he had invented. The Rudders teamed up with Davison and Hargraves in San Francisco and travelled up the Sacramento and Yuba Rivers to Marysville and the nearby Foster Bay diggings. It is highly likely that they discussed the similarities of the Californian geography to that of the region around the Macquarie River and also the fact that others had already found gold in that area.

When Hargraves returned to Australia in January 1851 on board the Emma, he was intent on acquiring fame and fortune by becoming the first discoverer of payable gold in Australia. When he failed to obtain a government grant to finance a gold searching trip, he turned to his friend William Northwood who lent him £105 to purchase a horse and supplies. Now well equipped and aware of McGregor's earlier gold finds near Wellington, Hargraves headed west over the Blue Mountains and beyond Bathurst. At King's Plains (near present Blayney) he met Thomas Icely en route to Sydney from his property "Coombing Park" at Carcoar. Hargraves had intended to accept an earlier invitation by Icely to spend the night at "Coombing Park" on his way to Wellington, but Icely advised him to go instead to Lister's Wellington Inn at Guyong. After becoming lost, Hargraves finally reached the inn on February 10th.

Susan Lister, proprietor of the inn, was the widow of Hargraves' earlier employer, Captain John Lister. She didn't recognise the visitor at first but soon remembered the cabin boy on board her late husband's ship. The Listers had fallen on hard times. The captain had continued his shipping interests on the 340-ton barque Wave and from 1834 was master of the 311-ton barque Fortune, which travelled regularly between England and the colony. By September 1838, the Lister family had settled in Sydney where Captain Lister set up as a shipping agent; however his business ventures were unsuccessful and within five years he was declared insolvent and lost all family possessions and property. He returned to life at sea as captain of a schooner, the Perseverance, but in February 1844 the ship became stranded in the South Channel, Moreton Bay, and eventually became a total wreck: "All hands reached shore with difficulty, assisted by two aborigines".

In 1846 the Captain became the licensee of the Robin Hood and Little John Inn at "The Rocks" on the Wellington Road between Bathurst and Orange but in July 1850 misfortune again struck the Listers when the 46-year-old captain was accidentally killed when he fell from his waggon near Bathurst. By just a year, after all his vicissitudes, he missed out on the relative prosperity brought by the goldrush.

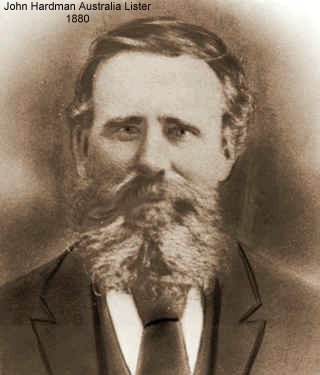

The young widow and her family moved a few miles farther west to Guyong, where she took over the licence of the Wellington Inn. When Hargraves arrived at the Inn some seven months after the Captain's death, he is said to have noticed on the mantelpiece rock samples collected from the local area by Susan's son, John Junior, now a young man of almost 23. These he suspected of being gold-bearing, and young John suggested that he could guide him to a place where he thought gold might be found. Hargraves' intended journey to Wellington was, for the moment, postponed and the scene was now set for the controversial "great discovery".

The Great Discovery

0n the morning of February 12th, 1851, with a packhorse and supplies provided by the Wellington Inn, and accompanied by the young John Lister, Hargraves proceeded down the Lewis Ponds Creek to a point four kilometres upstream from Yorkey's Corner. There, at the junction of Lewis Ponds Creek and Radigan's Gully, Hargraves told Lister, "Where you walk over now there is gold". The summer had been exceedingly hot and other creek beds in the area had dried out. This site provided them with the only available water for gold panning. After lunch, Hargraves washed six pans of earth, five of which produced tiny specks of gold. The excited Hargraves immediately had visions of grandeur, exclaiming, "This is a memorable day in the history of New South Wales: I shall be a baronet, you will be knighted and my old horse will be stuffed, put in a glass case and sent to the British Museum". Taking a piece of the Empire newspaper he wrote, "Gold discovered in the alluvial at Lewis Ponds Creek this 12th day of February, 1851".

Hargraves knew that more gold was needed to prove the existence of a workable goldfield, so he wanted to explore further afield. The most obvious place to search was the Macquarie River. But Lister was unfamiliar with that area, and suggested they get the help of his friend James Tom, an expert bushman and resident of the nearby Cornish Settlement. For eight exhausting days the trio searched with little success, Hargraves even trying his luck at Yorkey's Corner. On returning to the inn a verbal agreement was made: there would be no public announcement until a goldfield yielding more than £1 a day in wages was found. Hargraves then set off for Wellington, his original destination, returning in mid-March without finding any more traces of gold.

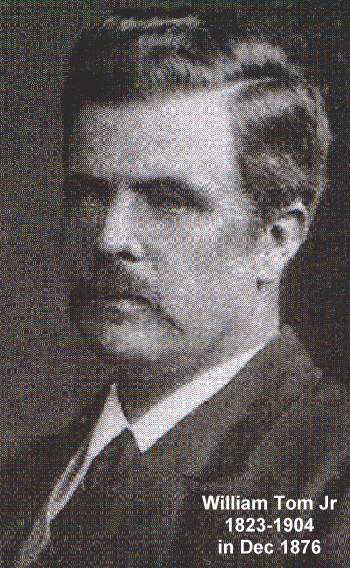

Before leaving Guyong for Moreton Bay (Brisbane), where he planned to continue his search for the elusive metal, the frustrated Hargraves suggested that a Californian Gold Cradle be constructed. James Tom then indicated that his younger brother William Jr., a skilled carpenter, would be the right man for the job. It was in the southern front room of the Tom family's homestead "Springfield", that William Jr constructed the first cradle.

The gold seekers, now a foursome, agreed that if any gold were found the profits would be shared equally. Hargraves, accompanied by Lister, left for Sydney on March 16th. Near Mutton Falls they prospected on the Fish and Campbell rivers without success and then parted company, Lister returning to Guyong. While Lister was absent, James, William and another Tom brother, Henry, secretly took the cradle for a trial run and in three days obtained 16 grains between them, enough to maintain their enthusiasm.

Meanwhile, Hargraves had his own hidden agenda. While in Sydney, with the sole intention of becoming the great discoverer of gold and indicating that a £500 reward was warranted, he secretly informed the Colonial Secretary, Edward Deas Thomson, of his find. Hargraves was told to put his claim in writing. The Colonial Secretary's response, dated April 5th, was: "In reply to your letter of the 3rd instant, I am directed by the Governor to inform you that His Excellency cannot say more at present than that the remuneration of the discovery of gold on the Crown Lands, referred to by you, must entirely depend on its nature and the value when made known, and must be left to the liberal consideration which the Government would be disposed to give it."

However, Hargraves' old friend Enoch Rudder had let the cat out of the bag by writing in the Sydney Morning Herald on April 4th, 1851, that "a goldfield has been discovered extending over a tract of country about 300 miles in length", a hint of what was to come. But it was not until William Tom Jr. and John Lister (James was away at the Bogan River on family business) made their significant finds between April 7th and 12th that proof of a payable field was obtained.

After starting out for the Macquarie River on the morning of the 7th, the two men decided first to try their luck at the junction of Lewis Ponds and Summer Hill creeks. William had heard about the nugget reputedly found there by the shepherd, Delaney. After the men had secured their horses and eaten, they began searching the creek bed. A few minutes later, on a rock bar below the junction (later called Fitzroy Bar), a 3/5 ounce gold nugget was found by William Tom Jr. The next day the cradle was fetched from its hiding place and put into use. "We carried the soil about 30 yards in two three-bushel bags, and in consequence could not keep the rocker in motion over about five hours each day". By the end of three days enough gold had been obtained to satisfy them that the ground would pay for working. Before returning home the two men decided to search further down the creek where Lister picked up a 2 ounce gold nugget snared in a tree-root. In total, about 4 ounces of gold had been obtained which included the 3/5 ounce nugget, a 1/4 ounce heart-shaped nugget and about 1 ounce of fine gold.

Hargraves was notified by mail and immediately hurried back to Guyong, arriving on May 5th. At "Springfield", the home of the Toms, the 4 ounces of gold was shared equally between the four. Hargraves then purchased the shares of his three partners, telling them they would be represented equally to the government.

There is little doubt that the naming of the discovery site as Ophir can be attributed to "Parson" William Tom, a Wesleyan lay preacher and William Tom's father, as he knew intimately the wording of the Old Testament: "Hiram brought gold from Ophir" and "They came to Ophir and they fetched from thence gold", phrases describing the city where King Solomon obtained his wealth.

When Enoch Rudder arrived the following day Hargraves asked him to purify some of the gold and make a specimen that would better impress the Governor. On May 8th Hargraves staged a meeting with some prominent citizens of Bathurst at James Arthur's Carrier's Arms Inn with the intention of making public "his discovery" and exhibiting his gold specimens, including the manufactured nugget. Three days later, accompanied by the Government Geologist Samuel Stutchbury, he was on his way back to Ophir to prove that gold existed there in abundance. Hargraves washed 21 grains of fine gold in three hours. Suitably impressed, Stutchbury wrote in pencil, apologising that no ink was yet available "in the city of Ophir", a letter to the Colonial Secretary dated May 19th, 1851 stating that "gold had been obtained in considerable quantity. The number of persons at work and about the diggings (that is occupying about one mile of the creek) cannot be less than 400, and of all classes .... I fear, unless something is done very quickly, that much confusion will arise in consequence of people setting up claims".

Referring to Stutchbury's visit, the Bathurst Free Press reported on May 17th, "The fact of the existence of gold is therefore clearly established, and whatever credit or emolument may arise therefrom, Mr. Hargraves is certainly the individual to whom it properly belongs." Hargraves had succeeded. Australia's first goldrush had begun.

For his "efforts" Hargraves received £10,000 and in 1877 an annuity of £250. In June 1851 he was appointed Commissioner of Crown Lands and supplied with a covered cart drawn by two horses and the services of two policemen. The Victorian Government also awarded him £5000, of which he received £2381 before the petitioning of the Toms and Lister ended the flow of money. Furthermore he was showered with testimonials and presented with gifts and introduced to Queen Victoria while the Tom brothers and Lister were pushed into the background. A full length sketch of "Mr E. H. Hargraves, the discoverer of gold" by T. Balcombe could be purchased for the price of 3 shillings, this also adding to Mr. Hargraves' celebrity status. A "pure gold cup", valued at £500 and bearing the inscription Palmam qui meruit ferat ("The presentation of this magnificent testimonial"), was presented to Hargraves at a public dinner, but Hargraves himself had contributed much of the money "in order to make the motto more appropriate, and the testimonial more magnificent than the town of Sydney intended". With the intention of establishing a new discovery Hargraves had the cup melted down to create a nugget, but found out too late that "all that glitters is not gold". The "pure gold" cup largely consisted of lead and copper.

Some portion of credit for the discovery of gold must go to Hargraves, the brilliant publicist, for it was he who instructed William Tom Jr. and John Lister in the techniques of Californian gold washing and the making of the cradle and, as the Colonial Secretary put it, "fathered the golden baby" produced by Tom and Lister. But the controversy centres on whether or not he was the sole discoverer.

The Controversy

A letter, dated May 19th, 1851, was composed by Hargraves and forwarded to John Lister for him to sign. Hargraves also requested Lister send the letter on to the Sydney Morning Herald for publication. Hargraves hoped that with Lister's signature, the letter would prove, once and for all, that he was the sole discoverer of gold and would put to rest any claims made by the Toms and Lister.

"Gentlemen - A report having been spread abroad by some malicious person who evidently is jealous of Mr. Hargraves' great discovery to the effect that I was the party who made it and communicated it to him, I beg leave most unreservedly to contradict this false report, although having been upwards of two years searching for it at one time with two geologists, and mineralogists who told me there were indications but could not find the gold. Mr. Hargraves, during his explorations, called on me as an old friend of my late respected father, and in course of conversation he told me this was a gold country, and if I would keep a secret, he would combine [with] me. This I agreed to - he was as good as his word, and scarcely ever made a failure, - where he said gold was to be found, he found it. I neither understand geology or mineralogy - but I was convinced my friend Mr. Hargraves knows where and how to find gold, and all honour and reward in the late discovery belong to him alone. Indeed, few men would have done what he has, intersecting the country with blacks, sometimes alone, sometimes with my friend Mr. James Tom, and during his explorations, had rain set in, from the imperfect manner in which he was equipped, starvation and death must have been the result. Trusting you will give this publicity in the columns of your valuable journal.

I am, Gentlemen,

Your most obedient servant,

John Hardman Lister

P.S. - I have also heard it reported that Mr. Hargraves had not acted fairly towards me, - I beg most distinctly to state that in all transactions with that gentleman, he has acted strictly honourable with me and friends in the secret of the great discovery. Mr. Hargraves is now no longer connected with me or my party at Ophir, and wherever he may go he has my best wishes, and I believe of all who have known him in the district of Bathurst."

Lister declined to sign the letter which was published in the Bathurst Free Press in January 1852, along with Lister's comments on the subject. "I could not subscribe my name to the untruths it contained ..... I also assert in plain words that Mr. James Tom and I never travelled with Mr. Hargraves with any other understanding than that we were his prospecting colleagues and concerned equally with himself in any favourable results that might accrue from our journey or journeys."

The Toms and Lister, disappointed and angry, began the long process of lobbying the government for recognition, a persistence that would endure for 40 years. William Tom had written to the Colonial Secretary, Deas Thomson, on June 6th, 1851, but the reply was anything but encouraging, Hargraves had failed to make any mention of his partners. Again, on December 22nd, Tom wrote a letter, but this time addressed it to Governor Fitzroy. The letters contained the Toms and Lister versions of the "facts" of the discovery and emphasised that they were considered "prospecting colleagues" of Mr. Hargraves and "that we are not altogether unwarranted in requesting some remuneration from the government for the expense we of necessity incurred, in developing one of the richest pecuniary resources of the colony". These letters were published in the Bathurst Free Press on January 1st, 1853, along with other inflammatory material. However, it must be considered that the Toms and Lister were not completely forgotten, for when the plan of the town of Ophir was drawn up in late 1851, the names of Lister Street and Thom (sic) Street were included, along with Hargrave (sic) Square.

The claims of John Lister, William Tom Jr and James Tom were finally heard before a government appointed Select Committee in June and July 1853. Hargraves was also called to give his version of the discovery. Throughout the hearing Deas Thomson appeared to be most supportive of Hargraves, directing questions that enhanced his claims. Hargraves could not have wished for a more influential patron.

The outcome of the proceedings was that William Tom Jr, James Tom and John Lister were granted a £1000 reward which was to be divided between them. They were recognised as having played a part in the discovery of payable gold but not as the actual discoverers. Simpson Davison and Enoch Rudder, the two early associates of Hargraves, who had also been conveniently cast aside and forgotten, published their own accounts of the gold discovery and its aftermath. Both claimed that the Hargraves' view, that gold existed in Australia, had in fact been their observation, which they had discussed with Hargraves while in California. Davison's book criticised the Colonial Secretary for not considering claims other than Hargraves'.

On February 11th, 1852, the eve of the first anniversary of the "discovery", were the events in question playing heavily on the mind of James Tom? James and his younger brother, Wesley, were on their way to their cattle station when they stopped at Peisley's Coach and Horses Inn at Orange for some liquid refreshment. James became intoxicated. They left for Heifer Station, situated only a short ride from Orange, set up camp and placed their horses in a nearby paddock. When Samuel Dickson, the owner of the paddock, arrived with two others and tried to impound the horses, a fight broke out during which Dickson was stabbed (superficially, however, and possibly by himself). Nevertheless, James Tom was indicted for stabbing with intent, but the jury, after four hours of deliberation, remained undecided and the accused was set free. "C. H. Green and J. T. Lane Esqs., J.P.s, both testified to the prisoner's general quiet and orderly character, and a paper was put in signed by eight or nine of the most respectable gentlemen in the district speaking in a similar strain."

The lobbying continued after 1854, letters appearing from time to time in the local and metropolitan newspapers. William Tom Jr never rested on the subject, persistently badgering the government while continuing his farming interests at his property, situated not far from the Cornish Settlement, now called Byng. His brother James married and moved to Chiltern, Victoria. John Lister married Ann Arthur on November 1st, 1860. Ann was the daughter of James Arthur, owner of the Carrier's Arms Inn at Bathurst and the Robin Hood and Little John Inn at the Rocks, the inn that Lister's father, the captain, had leased from Mr Arthur years before. Lister continued to live at Guyong where he grazed cattle, moving about 1870 to the Turon area to mine and prospect. At one time he conducted a general store at Lewis Ponds and by 1883 was working as a butcher back at Guyong and then at Lucknow.

Meanwhile Hargraves' celebrity status continued. In 1854 he was presented to Queen Victoria, made a member of the Royal Geographical Society and published a book, "Australia and its Goldfields". He had a house built at Noraville, near Gosford, where he often entertained the elite. The house was a replica of his place of birth, complete with a flagpole that flew the flag at half-mast when he was not in residence. The government rewards and appointments, the testimonials in his honour, the gifts and publicity, ensured Hargraves had the lifestyle he had once only dreamt about.

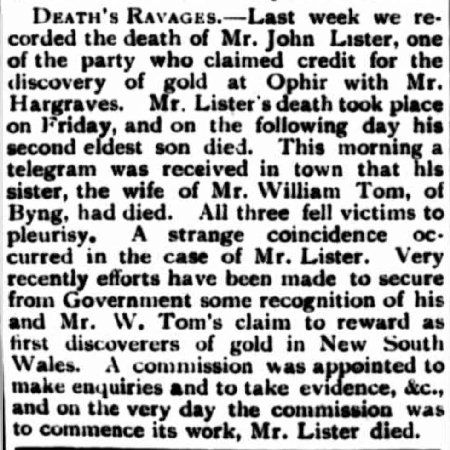

Finally in August 1890, the government appointed a second Select Committee to consider once again the claims made by the Toms and Lister, who were now men in their 60s. Thirty-nine years had passed since the gold discovery at Ophir. Their constant pressure on the government had finally paid off. However, the passing of time had not improved Lister's luck. On the very day he was to give evidence, September 17th, 1890, he died from influenza, a disease that would, in the next eight days claim the life of his son, Charles, daughter, Eveline, and sister, Sarah, who was the wife of William Tom Jr.

The committee's verdict was handed down on December 17th, 1890 and, at long last, recognised the petitioners as "undoubtedly the first discoverers of payable gold in Australia". At the same time credit was given to Hargraves for having taught them how to use the dish and cradle. Because, following the discovery, there had been a substantial improvement in trade in the colony, the committee indicated that the petitioners had not been adequately rewarded.

However, when the report came before Parliament for consideration in December 1890, it was defeated by 39 to 23 votes. Hargraves died on October 29th, 1891, without knowing the outcome. In 1898 William Tom Jr and two of his brothers exhibited the original gold cradle and a nugget at the Bathurst Show for a one shilling entrance fee. There were not many interested, apparently, as by the time the display had moved on to the Orange Show the price had been lowered to sixpence (letter from Charles Tom to his brother James.) The heart-shaped nugget that was found at Summer Hill Creek in April 1851 had been returned to William Tom Jr years before. Today it resides in a bank vault at Orange and is the property of the Orange Historical Society.

However, when the report came before Parliament for consideration in December 1890, it was defeated by 39 to 23 votes. Hargraves died on October 29th, 1891, without knowing the outcome. In 1898 William Tom Jr and two of his brothers exhibited the original gold cradle and a nugget at the Bathurst Show for a one shilling entrance fee. There were not many interested, apparently, as by the time the display had moved on to the Orange Show the price had been lowered to sixpence (letter from Charles Tom to his brother James.) The heart-shaped nugget that was found at Summer Hill Creek in April 1851 had been returned to William Tom Jr years before. Today it resides in a bank vault at Orange and is the property of the Orange Historical Society.

The controversy was born on the day that Hargraves and Lister found "first gold" at the junction of Lewis Ponds Creek and Radigan's Gully. How much gold did Hargraves actually obtain on February 12th, 1851? While Hargraves emphasised his claim, the supporters of the Toms and Lister played down the find. Hargraves stated that he washed 5 pans and obtained "about as much as would lie on a threepenny piece". This is, no doubt, an exaggeration, as other statements claim different results. John Lister, for example, stated Hargraves "washed 7 pans of earth and procured six very fine colours of gold", so fine in fact that "Hargraves placed a glass tumbler over it to make it look larger and prevent it from blowing away". Mrs. Bates, Lister's sister, claimed, "There were 3 specks and they were so small I could not see them distinctly with the naked eye", and Lister's wife exclaimed, "Oh, I do see a few almost invisible specks".

Contradictory as the claims may be, it would seem that the gold found by Hargraves had been a minute amount and that he had exaggerated the find in his quest for fame and fortune.

William Tom Jr, the last surviving gold discoverer and the most active of the petitioners, died on July 3rd, 1904, at Guyong, and is buried in the little cemetery at Byng. It was William who had written most of the letters to the government and to the press, badgering and rallying support for recognition of himself, his brother and Lister as the true discoverers of payable gold in Australia. No doubt, he was also bitter about the financial reward, a paltry sum compared to that received by Hargraves. There would be no mention in history books of the part John Lister, James Tom and William Tom Jr had played in the discovery. Nearly every child in Australia would learn that Edward Hammond Hargraves was the first to discover payable gold in Australia.

For 72 years there was no plaque or monument at Ophir to celebrate its historical significance, one reason being the fear of re-kindling the emotions of the Tom and Lister factions, who were still well represented in the area. In this time Ophir had become largely forgotten. Orange town clerk Frank J. Mulholland succeeded in gaining the support of Member for Bathurst, John C. L. Fitzpatrick, for his plan to commemorate the Ophir historical site with a monument. The site was surveyed byMines Secretary R. H. Cambage and advice on the area was supplied by long time Ophir resident and miner, James Uren. James, who was often referred to as the "Mayor of Ophir", helped select and prepare the site for the obelisk. The inscription was carefully worded to avoid adverse reaction and the names of the gold discoverers were listed in alphabetical order. A December date for the unveiling was selected to coincide with the town of Orange's annual celebrations, "Back to Orange Week".

The obelisk at Ophir was unveiled on December 28th, 1923 by Fitzpatrick, who by now was Minister for Mines, at a site near Fitzroy Bar. The inscription reads:

"This obelisk was erected by the New South Wales Government to commemorate the first discovery in Australia of payable gold, which was found in the creek in front of this monument. Those responsible for the discovery were Edward Hammond Hargraves, John Hardman Australia Lister, James Tom, William Tom.

From experience gained in California, Hargraves formed the idea that the district was auriferous and he found the first gold on 12th February, 1851, about two miles up Lewis Ponds Creek. He explained to the others how to prospect and make use of a miner's cradle, and Lister and William Tom found payable gold between 7th and 12th April, 1851."

The unveiling of the obelisk was attended by over 300 people who arrived at Ophir via what was described as "15 miles of the roughest road in the Orange district". The transport included horse-drawn buggies and sulkies, and seventy motorcars. Others arrived on horseback, some even making the journey on foot. Several of the old diggers were present, including James Eades and Bob McConnell and the Hargraves, Lister and Tom families were represented by relatives who travelled long distances to be there. Included were Mr. H. Hargraves (grandson) and Mr. Dudley (grand-nephew) of Edward Hammond Hargraves; John Hardman Lister and Arthur Lister (sons), Mrs W. H. Stephens (daughter) and Mrs. John Clemon (daughter) of John Hardman Australia Lister; Leslie Tom (grandson) and Miss Glennah Tom (great-granddaughter) of William Tom Jr.

But even the unveiling of the obelisk in December 1923 did not put an end to the bitter feelings about Hargraves' failure to recognise the brothers Tom and John Lister as co-discoverers of payable gold in Australia.

In January 1924 a letter was written to the Herald by Selina Webb (née Tom), second youngest daughter of William "Parson" Tom, who, as a 15-year-old, had been one of those present when Hargraves visited "Springfield". Although she was now well into her 80s and much of her letter has been shown to be historically incorrect, her passion on the subject was still evident.

Sir, I am the only person living who knows all about the arrangements at Springfield, re gold discovery. I was fifteen years old at the time. Mr Hargraves and Mr Lister came to Springfield one day, and said they were going to look for gold, and asked my brothers to join. Mr Hargraves had just returned from California, where he had been gold digging, and he thought some of the parts of Australia were like the gold bearing country in California. He was very jubilant, and in conversation (I was present at the time) said to my mother, if payable gold was discovered he would be made a baronet, and my brothers and Mr Lister would be knighted.

The four of them went off with pack horses, dishes, etc., and provisions to Lewis Ponds, 14 miles from Springfield, and searched for about a week. (My brothers, after the gold discovery, named the place "Ophir".) In a week they returned, and Mr Hargraves told my mother he had found enough gold to ruin the country, but not enough to do it any good. Mr Hargraves gave my mother the gold they had found - a small marking ink bottle about half full - which my mother afterwards gave me, and I passed it on to my son-in-law many years after. Mr Hargraves taught my brother William how to make a cradle, and how to use it, and he made this arrangement with them, that if they found payable gold they were to send it to him, and he would go to the Government to seek a reward, which was to be equally divided among the four. If they were not successful in finding payable gold, he intended returning to California, as he had a wife and ten children to support. My brothers and Mr Lister were looking for gold about ten days, when they discovered the nugget. My father, Mr. William Tom, was going to Sydney, and he took the gold down and handed it to Mr. Hargraves, who had either taken his passage or was on the point of doing so for California. So this nugget of gold altered his plans. My brothers did not hear from Mr Hargraves, and my brother wrote to ask what he was doing in the matter. No reply came.

A paragraph appeared in the "S. M. Herald" saying that Mr. Hargraves had discovered payable gold, and that he had two or three men prosecuting the search. This aroused the indignation of the Tom family, as they were not his employees but his partners. The picture of Mr Hargraves and his horse being so excited at the gold discovery is merely a romance, as he never did discover payable gold. But the gold would not have been discovered at the time but for Mr. Hargraves, and therefore he is entitled to have his name first on the obelisk.

The controversy carried on into the next generation. William Tom Jr's son Lister Albert ("Alby") Tom (1854-1932) used to carry the original heart-shaped gold nugget in his waistcoat pocket and bend the ear of anyone who would listen regarding the lack of recognition of the Lister/Tom contribution to the discovery of payable gold in NSW. This 1922 photo shows Alby displaying his gold nugget, which now resides in a bank vault in Orange and is the property of the Orange Historical Society. The other person in the photograph is thought to be Alby's brother Alfred (1857-1933).

The controversy carried on into the next generation. William Tom Jr's son Lister Albert ("Alby") Tom (1854-1932) used to carry the original heart-shaped gold nugget in his waistcoat pocket and bend the ear of anyone who would listen regarding the lack of recognition of the Lister/Tom contribution to the discovery of payable gold in NSW. This 1922 photo shows Alby displaying his gold nugget, which now resides in a bank vault in Orange and is the property of the Orange Historical Society. The other person in the photograph is thought to be Alby's brother Alfred (1857-1933).

On 24 September 1890 the Bathurst Free Press reported as follows:

Epilogue

On 3 September 2020, the Sydney Morning Herald published the following article.History stands corrected: Smith, not Hargraves, first to discover gold in NSW

By Julie PowerFor 170 years all that remained of mineralogist William Tipple Smith was a quartz gold sample, an unmarked grave and a reputation as the fraud who claimed to have discovered payable gold before Edward Hargraves.

On Thursday the history that most Australian schoolchildren learnt about events leading to the NSW gold rush in 1851 was corrected.

An anonymous grave, previously known only as number 4929, section four, Rookwood Cemetery, was marked for the first time. It now reads: "William Tipple Smith, 1803-1852, Mineralogist, discoverer of Australia’s first payable gold and co-founder of Australia’s iron and steel industry."

A commemorative plaque also details Smith's contribution to Australian history, ending a decades-long fight by his descendants to correct the record.

"A wrong perpetrated by a corrupt colonial administration in 1851 has been put to rights by its successor, the NSW government, almost 170 years later," was how his descendant and author Lynette Silver summed it up.

Ms Silver found missing documents that proved Smith had sent gold nuggets to England and letters detailing his claims that in 1848 he had found a payable goldfield near Yorkeys Corner. Missing for decades, the letters had been filed under "M" for Sir Roderick Murchison (a prominent British geologist who encouraged Smith) instead of "S" for Smith.

Three years later in February 1851, Hargraves heard there might be gold in the hills west of the Blue Mountains. He only found a few specks, but that didn't stop him from boasting of it to the Colonial Secretary and asking for a reward.

Hargraves returned to look for more gold, helped by men who had been told where Smith had found gold. When one of the men relieved himself in a creek near Yorkeys Corner, Ms Silver said, something sparkled – and he found a gold nugget. After Hargraves had claimed credit and boasted miners would find nuggets as "big as your boot", thousands rushed to the goldfields.

Hargraves received a £12,000 reward from the government while Smith's life ended in poverty and misfortune. He had lost the use of his right arm before migrating to Australia; Ms Silver said a stroke then affected his left arm and speech, making it difficult to pursue his claim.

Smith had emigrated to Australia from Suffolk in 1835. In 1847, he went looking for gold on the western side of the Blue Mountains and he found it the following year. That same year he and partners produced Australia's first iron and steel at Mittagong. His company would later become BHP.

Well before Hargraves made his discovery, Smith had visited NSW's colonial secretary in early 1849 carrying a gold nugget as proof, and promising to reveal the location in return for £500 to cover his costs.

Nothing happened, though the colonial secretary later attempted to find the gold himself and buy the land.

Smith again appealed to the government to acknowledge his claim but was branded a liar. Ms Silver said "the pesky mineralogist presented them with a problem. The colonial secretary and the governor knew he was first to find gold, but they had come under criticism for losing millions in government revenue for failing to control the mineral rights."

At Thursday's ceremony, NSW's Minister for Local Government Shelley Hancock said that when she first heard about Smith she thought it couldn't be true. A former history teacher, Ms Hancock said she had taught about Hargraves in schools.

Convinced by Smith's descendant, Bill Hamburger, 91, of Sussex Inlet, Ms Hancock realised it had been "an outrage by a government" and had worked to "right the wrongs of the past".

The new headstone, costing $11,250, was funded by private donations, the NSW government, Rookwood and Bluescope Steel.

Smith's great-great-grandson, Mr Hamburger, was moved to tears by Thursday's ceremony.

"When I was attending primary school, my grandmother said if they try and tell you Hargraves was the first to discover gold, you tell 'em the truth."

Smith died from a third and final stroke on December 3, 1852, four days after learning that his appeal for justice had failed, Ms Silver said. He was survived by his widow and seven children.