John Thurtell, son of Thomas and Susanna Browne Thurtell and nephew of John and Anne Browne Thurtell (his mother was Anne's younger sister and his father was John's younger brother), was convicted and executed for the murder of William Weare, a notorious swindler. The Thurtell name was blackened, notwithstanding some public sympathy for the murderer, and as a result other members of his family changed their names to Turner, Murray or Manfred. The adverse publicity may also have been a factor in the emigration of many members of the family to North America, South Africa and Australia.

John Thurtell, son of Thomas and Susanna Browne Thurtell and nephew of John and Anne Browne Thurtell (his mother was Anne's younger sister and his father was John's younger brother), was convicted and executed for the murder of William Weare, a notorious swindler. The Thurtell name was blackened, notwithstanding some public sympathy for the murderer, and as a result other members of his family changed their names to Turner, Murray or Manfred. The adverse publicity may also have been a factor in the emigration of many members of the family to North America, South Africa and Australia.[The miscreants in the Thurtell family were not limited to the infamous murderer. A James Thurtell was transported to Australia and is the ancestor of most of the Thurtells in that country. He was born in 1811 in Norfolk. His trial was heard by the above-mentioned Thomas Thurtell, Mayor of Norwich, father of the murderer. Exactly where James the transported convict fits into the picture is not clear.]

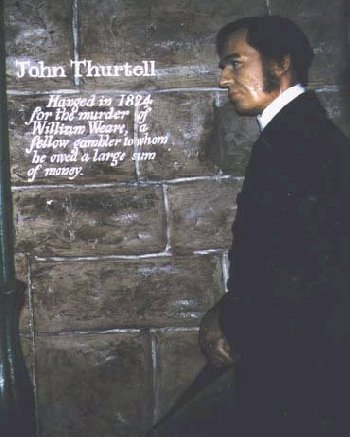

John Thurtell at Madame Tussaud's

| James Thurtell | ||

| Thomas Thurtell | ||

| John Thurtell | Winifred Nunn | |

| John Browne | ||

| Susanna Browne | ||

| Mary Skoulding |

| Event | Date | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Birth | 21 Dec 1794 | Place: England |

| Death | 9 Jan 1824 | Place: Hertford - public hanging |

John (alias "Jack") Thurtell, born 21 December 1794, in England, and hanged January 9, 1824, at Hertford, was the "black sheep" of the Thurtell family. He was the second surviving son of Thomas Thurtell, a prominent member of Norwich City Council, Norfolk, and (from 1828) Mayor of Norwich, and Susanna Browne.

The notorious Jack Thurtell became the subject of numerous books, articles, and plays. Much of what follows is taken from the 1987 book by Albert Borowitz, The Thurtell-Hunt Murder Case, Dark Mirror to Regency England.

Military Record

On 8 May 1809, at the age of 15, John Thurtell received a commission in Company 99 of the Royal Marines, based at Chatham, and was transferred a month later to HMS Adamant, the flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Edmund Nagle. After a few cruises in the eastern approaches to the Channel, Adamant was ordered to the Forth and lay moored in Leith Roads for several years, doing nothing.In July 1810 Lieutenant Thurtell was peremptorily discharged 'at the personal order of Nagle's successor, Rear Admiral William Otway, for some misconduct the nature of which is unknown'. However, he can't have been discharged absolutely from the service, as on 7 November 1811, he joined the 74-gun HMS Bellona (presumably still as a Marine). 'Despite its warlike name, the Bellona saw little more action than the Adamant. In early 1813 the ship proceeded to St Helena to pick up a convoy of East Indiamen returning from the Orient.'

When Thurtell's name became notorious a decade later, it was often asserted that he and his shipmates of the Bellona participated in the storming of the port of San Sebastián [on the north coast of Spain]. Eric Watson, however, found that on August 1, 1813, when San Sebastián fell, a muster of the ship was called at St Helen's on the Isle of Wight and that it cruised near San Sebastián a few days after hostilities had ended.

In early September the Bellona chased a brig of war and a schooner; the brig escaped, but the unarmed schooner was captured as a prize of war. These bloodless encounters with the enemy were apparently the only basis for Thurtell's later claims of gallantry under fire.

The Young Businessman

Jack resigned his commission as second lieutenant in June 1814 (when peace was signed) and in the following year, when he reached the age of 21, his father set him up in business as a manufacturer of bombazine, a twilled silk dress fabric, in partnership with one John Giddings (or Giddens). At this point he became interested in prize-fighting and formed a friendship with a prize-fighter who had moved to Norwich from London. When Jack himself went to London he hung out 'amongst other sporting characters' (according to Pierce Egan) 'at the various houses in London, kept by persons attached to the sports of the field, horse-racing, and the old English practice of boxing. He was well known to be the son of Alderman Thurtell, of Norwich, a man of great respectability, of considerable property, and likewise possessing superior talents. John Thurtell was ... viewed as a young man of integrity.'Unfortunately, Jack then blotted his copybook by going into London to collect several thousand pounds for goods sold to a firm there, which he owed to creditors of the partnership in Norwich, and claiming on his return that he had been robbed of the money by footpads.

Jackson's Oxford Journal of Saturday, February 3, 1821, Issue 3537 reports:

London, Jan 30

"On Monday evening Mr. J. Thurtell, of Norwich, was enticed by a fabricated note, just as he arrived from London by the day coach, to call on a Mr. Bolingbroke, near Chapelfield: on his returning, a woman accosted him, whom he did not know, and while walking along with her he was violently struck in the face by some person, and knocked down and robbed of 1508 l. in notes: his pocket, containing the property, was cut open, and a wound was inflicted in the right side, apparently done with a pen-knife. Mr T. was taken so unawares and so severely struck, that he was stunned, and had no power to defend himself. The evening was so extremely dark and foggy, that he could not distinguish the woman's face. Mr. T. had taken the above sum from Messrs. Leaf and Co. of London, to whom he had sold a large quantity of bombasin goods. It is hoped that as 13 of the 100 l. Bank of England notes are endorsed with Mr. Thurtell's name, the villains will be detected."

The creditors didn't believe him, despite his displaying bruises, a black eye and a cut on the head, and the Thurtell-Giddings partnership went bankrupt in February 1821, being unable to obtain any more credit.

That same year, Jack's brother Tom Thurtell, who had started out as a farmer, also went bankrupt. He owed £4000, but half of it was to his father. He attributed his bankruptcy to the poor state of the land he took on, bad crops and excessive taxation.

The "Swell Yokel"

Around this time, the brothers, both undischarged bankrupts, moved to London, though much of what they "did" seems to have been done by Jack alone, often using Tom's name, so, apart from his stint in prison, Tom may never actually have lived in London. He went back to Lakenham as soon as he could.In March 1822, Jack arranged for Tom to be thrown into the King's Bench prison for a debt of £17. This appears to have been an attempt to get Tom's bankruptcy discharged by taking advantage of 'the act for the relief of insolvent debtors'; it was an unsuccessful move, so Jack withdrew the complaint and Tom was released in April 1823 after 14 months in jail.

In the meantime, Jack had taken the lease of the Cock tavern in the Haymarket in Tom's name, but seems to have run it himself. Tom's credit may have been better than Jack's because he only really owed money to his father. In fact, Tom seems to have been pretty much a pawn in Jack's plans.

Jack Thurtell had an interest in several gambling houses and a tavern called "The Black Boy". Being himself an excellent amateur boxer, he trained and managed prizefighters.

As a sideline the Thurtells decided to embark on a method of fraud, the "long firm" scheme, in which goods are bought for credit and sold for cash and then the promissory notes given to the suppliers are dishonoured at maturity. It looks as if the whole point of leasing the Cock Tavern was to raise about £450 for the original investment in bombazine for the warehouse by selling off the contents of the cellar.

At the end of 1822 they insured a warehouse full of their bombazine goods with the County Fire Office for £1900, swiftly transferred the stock elsewhere and sold it at a discount. The warehouse was then completely destroyed by fire on 26 January 1823, Jack Thurtell having arranged for alterations to be made to it beforehand so that no-one could see the fire inside until it was too late. Various people noticed that the remains of the warehouse seemed to contain no burned bales of silk and the joinery work he had commissioned shortly before, which seemed to have no purpose other than to prevent the fire from being seen by the nightwatchman, struck people as very suspicious. The County Fire Office refused to pay the claim, and Tom Thurtell sued them. He won his case in June 1823, but Barber Beaumont, managing director of the County Fire Office, refused to pay out and procured an indictment against the Thurtells for conspiracy to defraud the insurance company. [Tom Thurtell apparently went to prison for fraud in 1824, after Jack was hanged, and served 3 years.]

A number of reports as to the fraud case appeared in The Times.

On the Run

At this point (for lack of the expected £1900) the finances of the Thurtell brothers collapsed yet again and they had to abscond from the Cock Tavern 'not only to excape its final collapse under a mountain of unpaid bills but to avoid arrest on the conspiracy charge, which appeared imminent because of their inability to raise bail'. They went into hiding at the Coach and Horses in Conduit Street.By this time, Jack Thurtell appeared to be suffering from 'an observable disintegration of his personality' (although he had always had a spectacularly explosive temper) and spent most of his time brooding on his wrongs and his grievances against all the people he felt had done him an injury, most particularly (according to Joseph Hunt) the ex-waiter and cardsharp William Weare, 'who in cheating him at cards had not only stolen his money [£200] but had made him the laughingstock of London's gamblers'.

Revenge

Jack decided to exact revenge. On 24 October 1823 he lured Weare out of London to spend a shooting weekend at the house of a friend, Bill Probert, at Radlett in Hertfordshire. Another friend, Joe Hunt, had agreed to help to murder Weare, and he and Probert were supposed to be following close behind Jack and his victim. In the event, however, they got cold feet and delayed so long on the road from London that, by the time they finally arrived in Radlett late in the evening, Jack had already committed the murder. At the bottom of Gills Hill Lane, after firing a shot that apparently missed, he had killed Weare by smashing in his skull with the muzzle of his pistol. Probert and Hunt merely had to help him to get rid of the body. Having dumped it overnight in a pond in the grounds of Probert's house, Gills Hill Cottage, they finally disposed of it in another pond beside the road to Elstree.Unfortunately for the success of his project, Jack had not covered his tracks very well. Firstly, Weare's associates in London knew that he had intended to spend the weekend in the company of Jack Thurtell and raised the alarm when he failed to reappear. Secondly, on the night of the murder Jack had stashed the murder weapon in a hedge and was not able to find it the next morning before it was discovered by some roadmenders and handed to the authorities. When enquiries were made about the disappearance of Weare, the matching pistol of the pair (which he had recently bought) was found in Jack's lodgings. Thirdly, for his trip to Radlett, Jack had made the mistake of hiring a gig drawn by a very distinctive iron-grey horse with a white face, which meant that several people remembered seeing it and it was possible to establish who the occupants had been. Finally, the fact that Probert and Hunt had not actually been involved in the murder itself meant that as soon as they realised that they were coming under suspicion they both turned King's Evidence and told the authorities everything they knew.

Probert was granted a pardon but Hunt, who had told lies in an attempt to conceal the fact that he had originally agreed to help in the murder, was refused a pardon, found guilty of being an accessory after the fact and transported to Australia. In fact, until the last moment, he was convinced he was going to share Thurtell's fate and wrote a farewell letter to his mother (62 KB), as reported in The Times, 13 Jan 1824. In the event, he survived until 1861 in Bathurst, NSW, where he married a doctor's widow, had two children and became a pillar of the local community. His descendants in Australia are now numerous.

Trial and Dispatch

Jack Thurtell, as described in the Borowitz book, was intelligent and very well spoken and always described his mother as very loving. At the time of the trial (see interview [184 Kb] with Pierce Egan, published in The Times, Tuesday 9 Dec 1823), he swore that he was innocent, but he later stated, "I am quite satisfied, I forgive the world; I die in peace and charity with all mankind... I admit that justice has been done me." (This is from the 1824 book by Pierce Egan Account of the Trial of John Thurtell and Joseph Hunt and Recollections of John Thurtell quoted in the Borowitz book). The Egan piece elicited an irate response, published 12 January 1823, from John Barber Beaumont, the managing director of the County Fire Office who was pursuing the fraud allegation regarding the Thurtell brothers' warehouse fire. Thurtell seems to have expected his trial to be delayed so that he could call three more witnesses who had been intimidated, he claimed, by prejudicial press reports. In the end, his side of the story was never fully told and has largely to be reconstructed from the evidence of Probert and Hunt. In the Albert Borowitz book, there is a pencil sketch of Thurtell's profile made during the trial by W. A. Mulready; it is reproduced here.

Thurtell seems to have expected his trial to be delayed so that he could call three more witnesses who had been intimidated, he claimed, by prejudicial press reports. In the end, his side of the story was never fully told and has largely to be reconstructed from the evidence of Probert and Hunt. In the Albert Borowitz book, there is a pencil sketch of Thurtell's profile made during the trial by W. A. Mulready; it is reproduced here.

Jack Thurtell was hanged at Hertford jail on 9 January 1824 (see report [859 KB] in The Times of Saturday 10 Jan 1824). His partner in crime, Joe Hunt, also gave his own account (252 KB) of Thurtell's last days, which was published in The Times.

There is a great deal of information on John Thurtell, including various books. There were also Broadside Ballads written about him as a "Caution to the Youth of Great Britain". William Makepeace Thackeray, was quoted as referring to the case as a "godsend" to journalists. Murder was rare in Regency England, and this was an extremely brutal murder committed by the son of a prominent merchant and Mayor of Norwich. The crime was also used as a cautionary tale of the story of a respectable young man who had gone to London and become involved with boxing and gambling, which were two of the unlawful pleasures of England at that time. The case has been called England's "most literary murder", with wide coverage in the press, poetry, plays, stories, books, and even the internet from 1823 to the present. Lurid scenes such as "the use of a ghost-faced horse to drive the gig on the night of the murder, a double water burial, an uncanny nocturnal disinterment, and a suspicious wife spying on the division of the criminals' spoils" (quotation from the Borowitz book) gave the murder "concrete visual images".

Some details of Jack Thurtell's life are given in the Dictionary of National Biography. A wax figure of him was displayed in Madame Tussaud's for about 150 years (see image above). It is said that Thurtell's features were modelled by Madame Tussaud herself, so the figure has not been melted down but put into storage.

Remains

According to the above-mentioned interview in The Times, Jack was fully expecting that the "process of dissection" would be carried out after his death - indeed the law required it - and hoped that what was left of him would be interred in a tomb over which his mother could shed a tear. The Times of 13 Jan 1824 carried a report (75 KB) of the public viewing of his corpse. His skeleton, so far as we know, is still at the Royal College of Surgeons, London.In the old days in England, it was customary after some of the more spectacular executions for the criminals not only to be publicly dissected but for their skins to be flayed from their corpses and tanned like cowhide. Two famous murderers who received this treatment were William Burke, the body snatcher, and Corder of the "Red Barn". Corder's skin, or part of it at least, was used to bind a two-volume account of his trial. His skin was sold at private auction, and someone bought a big enough piece to have a tobacco pouch made. (Crimes And Punishment: The Illustrated Crime Encyclopedia, Volume 17).

Burke's skeleton is still standing in the Anatomical Museum of Edinburgh University, while those of Corder, Jonathan Wild, and Eugene Aram are kept along with that of John Thurtell at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.