There was no conscription in Australia during World War I for overseas service (despite PM Billy Hughes' best efforts, it was narrowly rejected in a referendum in October 1916 and again in 1917), but there was strong community and peer pressure on young men to volunteer. This "encouragement" sometimes took the form of a white feather sent through the mail. Some say that Sid may have received such a feather from a young lady of his acquaintance.

A railway website records as follows:

Sidney Harold Tom LISTER, (service number 7069) was born on 11 October 1895 at Orange. He had begun working for the NSWGR on 14 July 1913 as a temporary Junior Porter in the Sydney District. He became permanent a month later, and an adult Porter on his 21st birthday in 1916. It was from this position that he was released on 10 August 1917 to join the Expeditionary Forces. Lister enlisted at Sydney the same day, citing his continuing service of 3.5 years with the 3rd/4th Infantry and nominating his father as his next of kin. Allotted to the 21st Reinforcement to the 17th Battalion he embarked on HMAT 'Euripides' at Sydney on 31 October 1917 and reached Devonport on Boxing Day. Lister proceeded ... to France on 1 April and was taken on the strength of the 17th Battalion on 16 April 1918. He lasted less than a month as he was killed in action in France on 14 May 1918. No details survive as to the circumstances or location of his death. He was buried 'in the vicinity of Morlancourt'. In the rationalisation of cemeteries after the war, Lister's remains were located, despite other information that there was a grave at Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, in their makeshift grave and exhumed. They were re-interred in Dive Copse British Cemetery, Sailly-le-Sec, France.

Thus in the closing stages of the war, on 14 May 1918, at the age of 22 years and seven months, the inoffensive railway porter who had attended West Marrickville Public School became one of 60,000 young Australian men sacrificed in the Great War to the requirements of the "Empire" (something like 2.5% of the male population of Australia at that time). This, of course, does not take into account the 150,000 wounded who made it home with shattered bodies and minds.

Cannon fodder, Fovant, Salisbury Plain, March 1918. Sid seems to be the soldier sitting up straight fourth from left between first and second rows.

Sid Lister's Brief Military Record

From the attached Casualty Form Active Service (apparently filled out at each step on the assumption he would become a casualty) and other documents, we glean that:

From the attached Casualty Form Active Service (apparently filled out at each step on the assumption he would become a casualty) and other documents, we glean that:

Private Sidney Harold Lister, Regimental no. 7069, was part of the 21st Reinforcement for the 17th Battalion [Australia was required by the Imperial General Staff to furnish 16,500 fresh troops each month, which was why Prime Minister Billy Hughes was pushing for conscription for overseas service].

He enlisted on 27 July 1917, was passed by the Medical Officer and arrived in camp on 10 August. On 29 August, he signed his Last Will and Testament, leaving "the whole of my Property and Effects to my mother Mrs Emily Australia Lister". On 31 October 1917, Sid was embarked at Sydney on H.M.A.S. "A 14". After a voyage of almost two months, he disembarked on 26 December 1917 at Devonport (Plymouth). This is where his Lister grandparents had last set foot on English soil on 19 April 1838, nearly 80 years before.

The next day he arrived at Fovant (a training camp on Salisbury Plain?) and four months later, on 1 April 1918, was transported to France, marching into "No. 1 Overflow Camp", probably near Le Havre in Normandy, that same day. From here, on 9 April, he marched out to his unit ("Beaumarais"??) and was "taken on strength" a week later on Tuesday 16 April. He was killed in action four weeks later on Tuesday 14 May.

The next day he arrived at Fovant (a training camp on Salisbury Plain?) and four months later, on 1 April 1918, was transported to France, marching into "No. 1 Overflow Camp", probably near Le Havre in Normandy, that same day. From here, on 9 April, he marched out to his unit ("Beaumarais"??) and was "taken on strength" a week later on Tuesday 16 April. He was killed in action four weeks later on Tuesday 14 May.

His "Effects received from the field" on 28 June 1918 by the AIF Kit Store in London were contained in a sealed parcel: Wallet, Photos, Cards, 2 Testaments, Diary, Metal Mirror, Small Religious Book. These items were sent on from Victoria Barracks, Melbourne, and Sid's mother signed the receipt for them on 20 February 1919. She also signed for "one Memorial Scroll and King's Message" on 8 August 1921. This signature reads "E.A. Lister for T.S. Lister" (her husband had died on 8 May 1920), and is accompanied by a note explaining her current address is "Unwin's Bridge Road, Undercliffe" (her daughter Dot's address). Sid's mother also received a Memorial Plaque which she deputed her daughter Dot Crawshaw, Sid's older sister, to collect on 3 January 1923. Finally, on 4 June 1923, she signed for "one Victory Medal in connexion with the late No. 7069 Pte. S.H. Lister, 17th Battn."

The Battle of the Somme

[Notes by JCC after a visit to Villers-Bretonneux and Dive Copse on 8 Oct 2002]

Only in the first few months and the last few months of World War I was there much movement. For 3½ years, the Western Front, stretching 750 km from the Channel to Switzerland was the scene of see-sawing trench warfare and unbelievable senseless slaughter. Actually, this was the "Western Front" seen from the German point of view. Erich Maria Remarque's haunting novel about bewildered German boys in the trenches, "Im Westen Nichts Neues", was translated by Arthur Wheen, an AIF veteran and later librarian at the V&A in London, as "All Quiet on the Western Front".

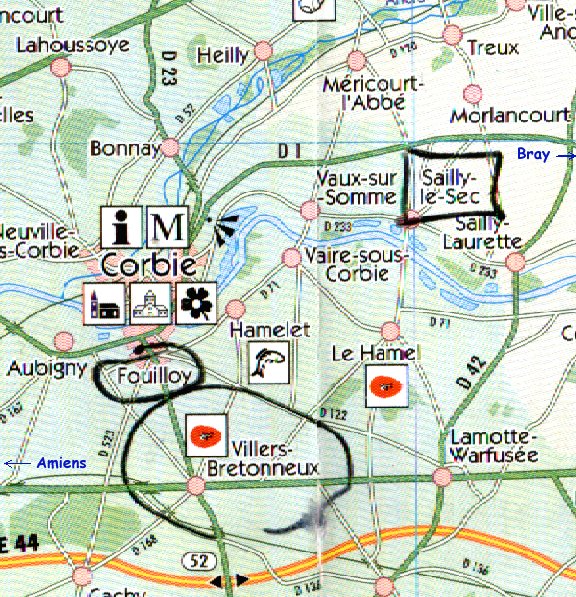

Picardy is wide, flat and empty, and thus ideal for set-piece battles. The main Battle of the Somme took place in July-November 1916 around the red line on the attached map. For the loss of 600,000 men, the Allies gained a few kilometres of mud. The Australians took part in that battle, but their main moment of glory came later, in 1918, when the Germans, beginning on 21 March, attempted a breakthrough and advance towards Amiens.

The Australian Imperial Force at Villers-Bretonneux

The German offensive was finally halted by the Australians on 25 April 1918 (the third anniversary of Gallipoli) at Villers-Bretonneux, a town which has had a soft spot for the Aussies ever since (or perhaps - and more likely - it's the other way round). This event is considered one of the most significant of the closing stages of the war. There is a major Australian war memorial north of the town on the road to Fouilloy. In 1993 an Unknown Australian soldier was disinterred from Adelaide cemetery on the western edge of Villers-Bretonneux for reburial in Canberra. (There is a plaque at the Australian National Memorial in Fouilloy commemorating the event, with the signature of the PM of the day, Paul Keating.)

The 2nd Australian Division, in a counter-offensive beginning on 8 August, then pushed on to Péronne which they took in a bloody battle on 2 September 1918. In the Villers-Bretonneux museum, there is a photo of a group of Diggers in the main street of Péronne, which they have rechristened "Roo de Kanga".

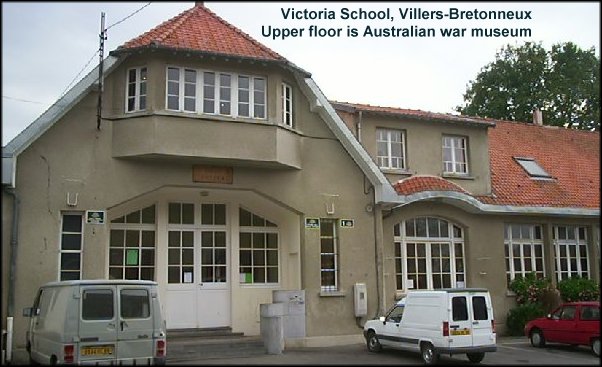

In 1927, with money donated by Australian schoolchildren, the Victoria School was built in Villers-Bretonneux. It still seems to be the main, or only, primary school in town, and also houses an interesting museum of WW I Australiana.

There are innumerable cemeteries and memorials all over the region, of the various nations involved, all very well kept, though there is no longer anyone to talk to - just a printed guide in a small cupboard at each cemetery with the names and locations of the dead, and a vistors' book to sign.

Sid Lister and Dive Copse

Sid Lister was killed on 14 May 1918 at Morlancourt to the north of Sailly-le-Sec. This does not seem to have been the date or the place of an important battle. His mate told the family that as he emerged from his trench, a marksman shot him in the forehead. He seems to have been buried temporarily near Morlancourt (see the black-and-white photo supplied to the family). The Dive Copse British Cemetery where he now rests was not retaken by the Allies until August. His Grave Reference is Panel Number: III. G. 12. In the guide and on his headstone is written:

In Memory of

SIDNEY HAROLD LISTER

Private 7069

17th Bn., Australian Infantry, A.I.F.

who died on Tuesday, 14th May 1918

SIDNEY HAROLD LISTER

Private 7069

17th Bn., Australian Infantry, A.I.F.

who died on Tuesday, 14th May 1918

The guidebook adds:

Private LISTER

Son of Thomas Sydney Lister and Emily Australia Lister of 32 Day St., Marrickville, New South Wales.

Native of Orange, New South Wales.

Remembered with honour

Son of Thomas Sydney Lister and Emily Australia Lister of 32 Day St., Marrickville, New South Wales.

Native of Orange, New South Wales.

Remembered with honour

Les Carlyon in The Great War writes:

The Australians in late April came up with a tactic they called 'peaceful penetration'. The noun was right enough; the adjective was absurd. Some called the tactic more sensible names, such as 'nibbling' and 'winkling'. Whatever it was, it worked. The Australians practised it on the Villers-Bretonneux front south of the Somme, around Morlancourt in the triangle between the Ancre and Somme rivers, and in front of Hazebrouck in French Flanders. The British divisions at this time were mostly content to hold their lines.So it looks as though Sid died while 'nibbling' at the German lines.

Peaceful penetration was about changing the line without the fanfare of a set-piece. It was about sniping, harassment, shelling with gas, the snatching of prisoners and playing on the Germans' nerves. It was a new form of the trench raid, but this time the raiders did not withdraw after doing as much damage as possible in the shortest amount of time. The Australians tried to hold the positions they had raided and often did. So the German line was pushed back fifty yards here and seventy-five there, night after night. Peaceful penetration was a way of saying that no new status quo should be allowed to develop, that the war had to be kept fluid. Monash, while still commanding the 3rd Division, forced the Germans back about a mile at Morlancourt with a succession of raids. He had always liked to take prisoners, whom he would sometimes interview in German. They were now sufficiently demoralised to want to talk freely, he wrote. Here was another big change in the war: the morale of the German army was finally in decline. This was one reason peaceful penetration worked so well.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission's website (www.cwgc.org) supplies the following historical information:

In June, 1916, before the Somme offensive, the ground North of the cemetery was chosen for a concentration of Field Ambulances, which became the XIV Corps Main Dressing Station. A small wood close by, under the Bray-Corbie road, was known as Dive Copse, after the name of the officer commanding the Main Dressing Station; and the cemetery was made by these medical units. Plots I and II were filled in the first three months' fighting. Plot III contains the graves of 77 men who fell in August, 1918 (when the cemetery, occupied by the enemy in the spring, was retaken), and of 115 whose bodies were brought in from scattered graves and small cemeteries in the neighbourhood. There are now nearly 600, 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this site. Of these, 30 are unidentified and four soldiers of the London Regiment and six of the Australian Imperial Force are known to be buried among them and their names are recorded on special headstones. The cemetery covers an area of 2,383 square metres and it is enclosed by a brick wall. The only considerable cemetery concentrated to Dive Copse was Essex Cemetery, Sailly-le-Sec. This burial ground was 914 metres further North, on the edge of the Bray-Corbie road. It was begun by the 10th Essex Regiment in August, 1918, and it contained the graves of 30 soldiers from the United Kingdom and three from Australia.

Dive Copse is a peaceful little cemetery, surrounded by ploughed fields, as far as the eye can see. It is on higher ground than Sailly-le-Sec, which is down nearer the river. The river Somme itself is a sad, sluggish thing, more like a series of billabongs than a real river - (could this be why the town is called Sailly-the-Dry?) - though when it rains as it did in 1918, it must fill out.

The cemetery contains the remains of 512 British, 59 Australian and 18 South African soldiers of WW I. Many were buried in 1916 early in the Somme offensive; then the Germans took control of the area again, until they were driven back in August 1918. According to the Internet text quoted above, Plot III contains 77 men who died in that effort, plus "115 whose bodies were brought in from scattered graves and small cemeteries in the neighbourhood".

Since Sid had died in May, while Dive Copse was held by the Germans, he must have been amongst these last. He would not, presumably, be one of the 3 Australians brought in from Essex cemetery 900 metres farther north, since that was only begun in August 1918. Most Australians were reburied at the large AIF war memorial at Fouilloy; why this was not so in Sid's case is not clear, but one can imagine the confusion which reigned in the immediate aftermath of the Great War.

Dive Copse is difficult to find coming from the Sailly-le-Sec direction. It is on an unmarked road leading up out of an intersection at the eastern end of town. On the other hand, it is signposted for anyone arriving from Sailly-Laurette. There is probably a signpost on the Corbie-Bray road, where there is also an Australian memorial.

Sid Lister remembered at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra.